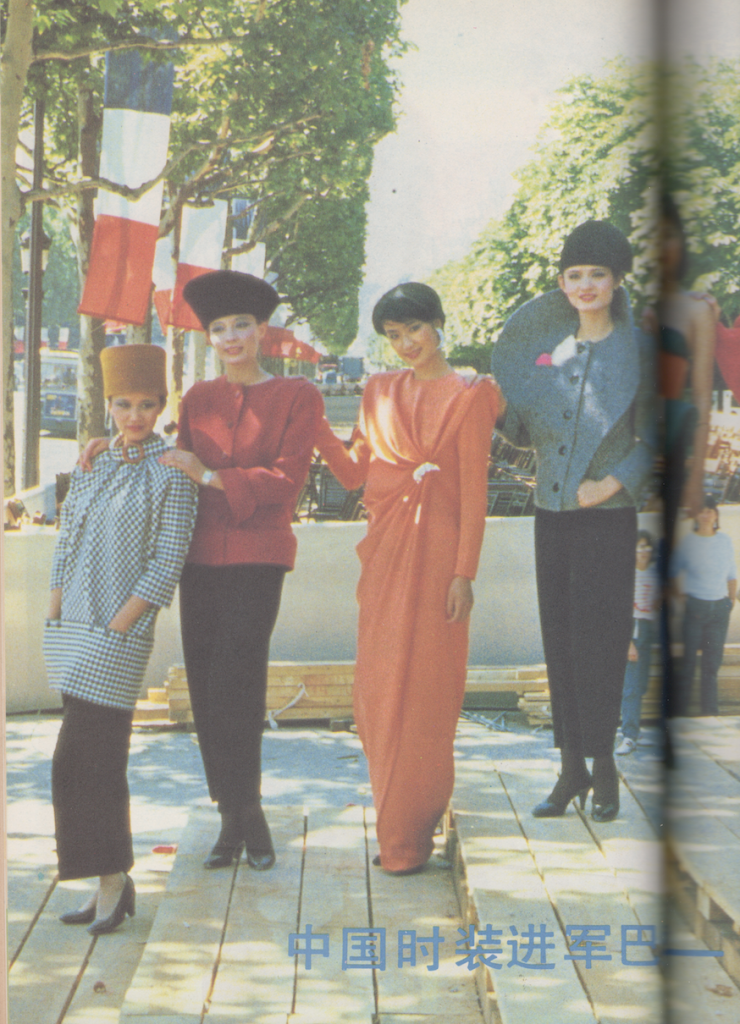

SOME THIRTY YEARS AGO on July 22, 1985, Pierre Cardin sent nine young Chinese girls down the runway of his show in Paris. The moment marked the significant changes that had occurred in Chinese fashion and its encounter with the West, as well as offering a glimpse of the future of China’s industry.

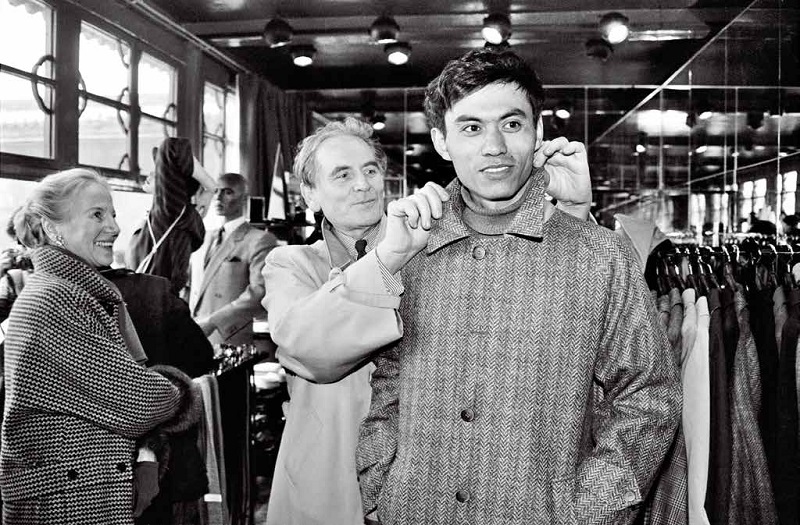

Cardin’s girls were the first Chinese models to travel overseas and walk for a Western designer, their arrival in Paris earmarked an event in cultural history. Yet, the fact that this had even happened was in itself the culmination of a much longer process Cardin espoused in 1979. Cardin’s contribution, and reason for his stature in narratives of Chinese fashion history, stems from his diplomatic relationship with the Chinese government. In 1976 China began to look seriously into expanding its textile and clothing industry and sought to consult with foreign designers. After being invited to China in 1978, Cardin was appointed Fashion Consultant by the Communist government. The role was, in the designer’s words, to ‘advise the Chinese on how to style their textile products to make them more marketable to the West.’1

Cardin’s relationship with China was for the country’s government, premised on economic considerations, but the designer was also enthused by the economic potential of the Far East, declaring: ‘if I can produce one button for every Chinese, that’s 900 million buttons.’2 Cardin envisaged that this new position could open up the possibility for Chinese manufactured ready-to-wear products under the Cardin label. Yet, the designer also saw the opportunity for bringing Western ideas on fashion to the Chinese public.

It was not as if China had no experience of fashion shows – Shanghai had seen the first back in 1909. Even after China turned Communist in 1949, there had still been a state-approved fashion show in 1956 before the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) ended such allegedly bourgeois activities. But the newly appointed Cardin proposed to put on the first fashion show by a Western designer in the People’s Republic of China, and he was determined to do it in grand style.

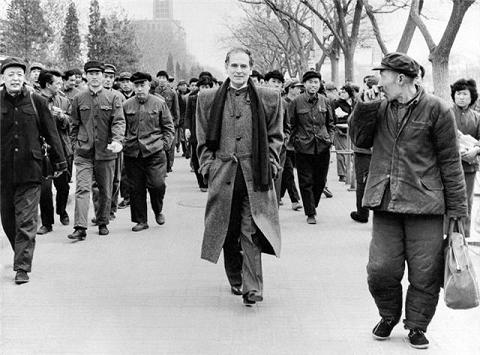

In 1979 he flew some two hundred and twenty outfits from his archive, and a dozen models to China, and unleashed them onto a Chinese audience wholly unprepared for what they were about to see.

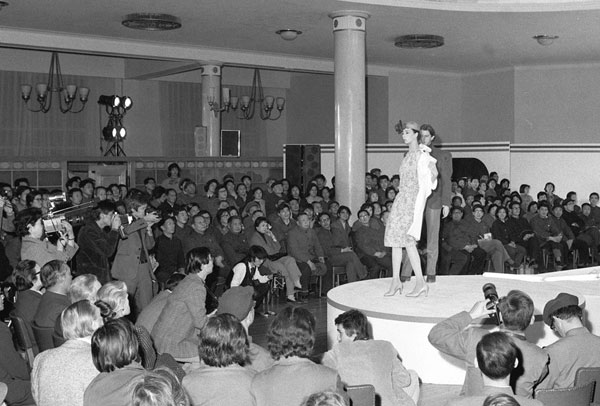

Chinese officials, uncertain of how the audience would react, banned the press from attending, and restricted those present to industry cadres.3 But naturally public and media interest was high, and journalists fought through a crowd to gain entrance. Inside, the audience was stunned into silence by the show. John Fraser, a Western reporter at the event, described what he saw: ‘see through blouses, dresses slashed down the side to expose the handsome flanks of Parisian models, gentlemen in thigh-tight pants, [and] space-age shoulder pads.’4 So exotic was the display that Western diplomats were shocked by the contrast to China’s sartorial norm: Mao suits. Cardin’s theatrics had succeeded in presenting a sartorial alternative to enforced uniformity of the Maoist era. They were post-Mao now, so Cardin offered a vision of post-Mao suit too.

Cardin followed this fashion show, and several others he staged subsequently, with entrepreneurial commercial ventures in China. By 1983, his designs were being manufactured in dozens of factories across the country. This development made sense to his business, which he continued to run from his Paris studio: labour was cheap, as were raw materials. Even so, Cardin’s plan to capitalise on China’s production advantages did not work out. The problem was that the Chinese were naïve to Western fashion economics. Buyers discovered that Chinese officials vastly overpriced Cardin-licenced products and insisted on high prices.

Nevertheless, Cardin had been successful in demonstrating that fashion was about much more than manufacturing. Though Chinese officials had been wary about the negative cultural influence of Cardin’s futuristic shows, it was the cadres from the textile and garment industry who were most affected. After holding shows in the late Seventies, Cardin proposed developing Chinese models to the officials who began the establishment of a ‘modelling team’ to present local fashion. Not long after, in November 1980, the Shanghai Garment Company duly assembled the first group of official Chinese fashion models. Chosen from workers in garment factories, these girls were selected with rigid criteria concerning their physical characteristics. Their selection represented the prevailing ideas amongst industry officials of an ideal appearance; according to Christine Tsui’s China Fashion: Conversations with Designers they had to be 1.64m in height, with a 80cm/60cm/80cm ratio in the bust/waist/hips.

For most of Chinese society, unfamiliar with Western fashion, the idea that women would display themselves and essentially use their bodies to sell clothing was unthinkable. Worse still, were the Western designs that were often considered vulgar by conservative Chinese (especially parents), many of which bore prominent shoulders, cleavage, and legs.

Apart from societal criticism, Chinese modelling in the early Eighties was not a particularly welcoming profession. Models were poorly paid and expected, not only to be fashion models, but model citizens and public identities to the PRC. As state-media bizarrely suggested in 1982, Chinese models were ‘working to promote the Four Modernisations rather than merely satisfying vulgar and inferior tastes.’5 With sport-like rigour, models had to undergo lessons in movement, makeup techniques, sewing and also physical fitness training. They were patronisingly named ‘fashion performance teams’ by Chinese officials. Yet, in spite of all this, the selection of trained models debuted in February 1981, at the Shanghai Friendship Movie Theatre, where the new models showed garments produced by the local Shanghai factories. This was precisely what the Shanghai Garment Company cadres had intended – Chinese models modelling Chinese-made products to foreign buyers.

In 1981 Cardin returned to China to stage his largest show ever at the Workers’ Stadium in Beijing, and with the direct support of Beijing’s Vice Mayor – who was, of course, happy to assist an ‘old friend’ of the Chinese government. This show, as it turns out, was on the right side of history. Chinese interest in fashion was by now on an upward trend: the country’s first fashion magazine, Shizhuang (translating to ‘Fashion’) was published in 1980, while the first degree program in clothing design had also been established. Fashion became a litmus test between the more conservative China, and the emerging, younger China.

Perhaps this dichotomy was only to be expected. The older generations had seen first hand during the Cultural Revolution how apparently progressive ideas could give way to radicalism – and violence. While the youth had grown up in an era of socialistic uniformity in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, a time that suppressed desires for individual expression. Cardin’s activities were in line with the more progressive and youthful sentiments in Chinese society, for both his and Chinese fashion’s benefit.

In subsequent years Western fashion in China went from strength to strength. Fashion benefitted from its coherence with progressive discourse as an expression of personal preference, and not ‘ideological principles’.6 Moreover, the Party itself seemed to be changing its mind and fashion became a vehicle for these narratives. In the Summer of 1983, the Shanghai modelling team received an invitation to stage a show for the Party leadership in Zhongnanhai – the heart of Chinese government in Beijing. This was unprecedented and never to be repeated, but their approval of the event soon became public. The Chinese Communist Party’s official mouthpiece, the People’s Daily, gave a ringing endorsement of the show with an editorial entitled ‘innovative fashion, brilliant performance.’7 Since the Party leadership themselves approved of fashion, then surely it could not be ‘bourgeois liberalism’ – or for that matter, immoral.8

Chinese fashion was beginning to come into its own. Other clothing and textile companies imitated the Shanghai example and developed their own modelling teams, as Chinese designers became more adventurous. In July 1984, the Liaoning Province Silk Corporation held its own fashion show in Beijing, sending out models – with ‘Thriller’ playing overhead – in what reporter Allen Abel called, ‘Punk Mao’.9 The show, which featured traditional Communist garb, such as People’s Liberation Army caps, refashioned in what was, in effect, a microcosm of the developments in Chinese fashion.

On 23 May 1985, Cardin returned to China to stage his largest show ever once again at the Workers’ Stadium in Beijing. More than 10,000 flocked to watch Chinese models display his latest collection – accompanied by a twenty-member orchestra – in a catwalk show that featured ‘bare midriffs, V-cut backs, velvet tuxedos, gowns with matching coolie hats’ and a white wedding dress with an extremely long train for the finale.10

Following the spectacular 1985 event Cardin sought to bring a group of Chinese models to Paris. He would dress them in qipao (traditional dress), and bring Chinese culture, and style, to the West. At Paris Fashion Week, Cardin, with permission from the Chinese government, sent the nine models onto the runway of his show the same year with tremendous results. As The Times of London noted:

‘Nine Chinese models stepped shyly out on the catwalk in Paris yesterday and stole the Pierre Cardin show. Cardin, who is helping the Chinese to turn their silk production into a fashion industry, hand picked the prettiest girls. But there was nothing Eastern about the clothes, which were all Parisian miracles of couture cutting – coats that grew into capes, ponchos composed out of pleats and the famous Cardin collars unfolding like lotus flower petals around the exquisite head of twenty-two year-old Shi Kai, a student from Beijing.’11

Shi Kai, in fact, closed the show for Cardin, wearing a ‘white brocade wedding dress.’12

Perhaps only Pierre Cardin could have managed to push Chinese fashion onto the global stage in this way since he had access to the platform to do so, and a unique diplomatic alliance with the government to use it.

Cardin did not see a profit on all his activity in China until later in the 1990s.13 But if there was a reward in all of this for the designer, it was in terms of something unquantifiable. Cardin helped to establish the Chinese fashion industry, and in so doing, changed the Chinese fashion industry, helping it become the giant it is today. While Cardin would eventually make money from his investment in the Chinese fashion industry, and his businesses in China would expand dramatically, his greatest achievement, and his great service to the Chinese, was to help lay the foundations for their cultural engagement with fashion.

Jin Li Lim is a researcher and PhD student on Chinese history at the London School of Economics.

Frank Prial, ‘China names Cardin as Fashion Consultant’, 08/01/1979, New York Times; ‘Landed pact with Chinese, Cardin says’, 09/01/1979, New York Times. ↩

Richard Morais, Pierre Cardin: The Man Who Became A Label, Transworld, London, 1991, p. 194. ↩

Under the PRC’s dual party-government system, where the Communist Party is at the heart of state and political power, a ‘cadre’ is an official, who, more often than not, is also a party member. ↩

Idem. ↩

Wu Juanjuan, Chinese Fashion: From Mao to Now, Berg, New York, 2009, p. 157. ↩

Wu Juanjuan, Chinese Fashion: From Mao to Now, Berg, New York, 2009, p. 15. ↩

This is my translation of《新颖的时装,精彩的表演》as quoted in, Meng Hong, ‘Xin zhongguo shoujia shizhuang biaoyuan dui’, Chuan cheng, No. 7 (2010), p. 9. ↩

Idem. ↩

Allen Abel, ‘Chinese fashion begins to shed drabness’, 30/07/1984, The Globe and Mail. ↩

‘New stores by Cardin’, 11/06/1985, Associated Press. ↩

‘Fashion (Paris fashion): Bonjour richesse’, 23/07/1985, The Times. ↩

Bernadine Morris, ‘The effect is lavish as Paris Couture opens’, 23/07/1985, New York Times ↩

‘In the world, my name stays at first—Pierre Cardin’, 28/12/2009, East Day. ↩