In the last chapter of Emile Zola’s Le Bonheur des Dames (The Ladies’ Paradise), Madame de Boves, an kleptomaniacal aristocrat, attends a sale at a department store owned by Octave Mouret. Zola based his portrait of 19th-century retail on the Paris department store, Le Bon Marché.

WHAT CAUSED THE LADIES to stop was the prodigious spectacle presented by the grand exhibition of white goods. In the first place, there was the vestibule, a hall with bright mirrors, and paved with mosaics, where the low-priced goods detained the voracious crowd. Then the galleries opened displaying a glittering blaze of white, a borealistic vista, a country of snow, with endless steppes hung with ermine, and an accumulation of glaciers shimmering in the sun. You here again found the whiteness of the show windows, but vivified, and burning from one end of the enormous building to the other with the white flame of a fire in full swing. There was nothing but white goods, all the white articles from each department, a riot of white, a white constellation whose fixed radiance was at first blinding, so that details could not be distinguished. However, the eye soon became accustomed to this unique whiteness; to the left, in the Monsigny Gallery, white promontories of cotton and calico jutted out, with white rocks formed of sheets, napkins, and handkerchiefs; whilst to the right, in the Michodière Gallery, occupied by the mercery, the hosiery, and the woollen goods, were erections of mother of pearl buttons, a grand decoration composed of white socks and one whole room covered with white swanskin illumined by a stream of light from the distance. But the greatest radiance of this nucleus of light came from the central gallery, from amidst the ribbons and the neckerchiefs, the gloves and the silks. The counters disappeared beneath the whiteness of the silks, the ribbons, the gloves and the neckerchiefs.

Round the iron columns climbed ‘puffings’ of white muslin, secured now and again with white silk handkerchiefs. The staircases were decorated with white draperies, quiltings and dimities alternating along the balustrades and encircling the halls as high as the second storey; and all this ascending whiteness assumed wings, hurried off and wandered away, like a flight of swans. And more white hung from the arches, a fall of down, a sheet of large snowy flakes; white counterpanes, white coverlets hovered in the air, like banners in a church; long jets of guipure lace hung across, suggestive of swarms of white motionless butterflies; other laces fluttered on all sides, floating like gossamer in a summer sky, filling the air with their white breath. And the marvel, the altar of this religion of white was a tent formed of white curtains, which hung from the glazed roof above the silk counter, in the great hall. The muslin, the gauze, the art-guipures flowed in light ripples, whilst very richly embroidered tulles, and pieces of oriental silver-worked silk served as a background to this giant decoration, which partook both of the tabernacle and the alcove. It was like a broad white bed, awaiting with its virginal immensity, as in the legend, the coming of the white princess, she who was to appear some day, all powerful in her white bridal veil.

‘Oh! extraordinary!’ repeated the ladies. ‘Wonderful!’

They did not weary of this song in praise of whiteness which the goods of the entire establishment were singing. Mouret had never conceived anything more vast; it was the master stroke of his genius for display. Beneath the flow of all this whiteness, amidst the seeming disorder of the tissues, fallen as if by chance from the open drawers, there was so to say a harmonious phrase, – white followed and developed in all its tones: springing into existence, growing, and blossoming with the complicated orchestration of some master’s fugue, the continuous development of which carries the mind away in an ever-soaring flight. Nothing but white, and yet never the same white, each different tinge showing against the other, contrasting with that next to it, or perfecting it, and attaining to the very brilliancy of light itself. It all began with the dead white of calico and linen, and the dull white of flannel and cloth; then came the velvets, silks, and satins – quite an ascending gamut, the white gradually lighting up and finally emitting little flashes at its folds; and then it flew away in the transparencies of the curtains, became diffuse brightness with the muslins, the guipures, the laces and especially the tulles, so light and airy that they formed the extreme final note; whilst the silver of the oriental silk sounded higher than all else in the depths of the giant alcove.

[…]

In the lace department the crush was increasing every minute. The great show of white was there triumphing in its most delicate and costly whiteness. Here was the supreme temptation, the goading of a mad desire, which bewildered all the women. The department had been turned into a white temple; tulles and guipures, falling from above, formed a white sky, one of those cloudy veils whose fine network pales the morning sun. Round the columns descended flounces of Malines and Valenciennes, white dancers’ skirts, unfolding in a snowy shiver to the floor. Then on all sides, on every counter there were snowy masses of white Spanish blonde as light as air, Brussels with large flowers on a delicate mesh, hand-made point, and Venice point with heavier designs, Alençon point, and Bruges of royal and almost sacred richness. It seemed as if the god of finery had here set up his white tabernacle.

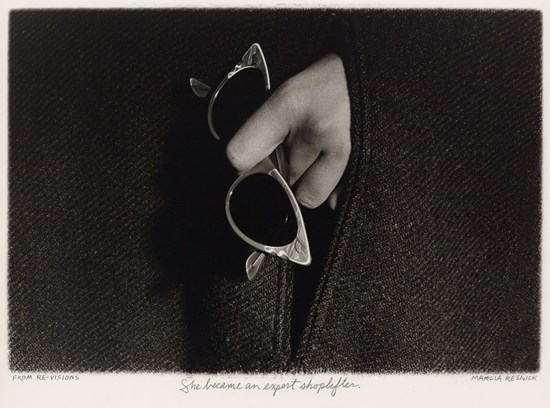

Madame de Boves, after wandering about before the counters for a long time with her daughter, and feeling a sensual longing to plunge her hands into the goods, had just made up her mind to request Deloche to show her some Alençon point. At first he brought out some imitation stuff; but she wished to see real Alençon, and was not satisfied with narrow pieces at three hundred francs the yard, but insisted on examining deep flounces at a thousand francs a yard and handkerchiefs and fans at seven and eight hundred francs. The counter was soon covered with a fortune. In a corner of the department inspector Jouve who had not lost sight of Madame de Boves, notwithstanding the latter’s apparent dawdling, stood amidst the crowd, with an indifferent air, but still keeping a sharp eye on her.

‘Have you any capes in hand-made point?’ she at last inquired; ‘show me some, please.’

The salesman, whom she had kept there for twenty minutes, dared not resist, for she appeared so aristocratic, with her imposing air and princess’s voice. However, he hesitated, for the employees were cautioned against heaping up these precious fabrics, and he had allowed himself to be robbed of ten yards of Malines only the week before. But she perturbed him, so he yielded, and abandoned the Alençon point for a moment in order to take the lace she had asked for from a drawer.

‘Oh! look, mamma,’ said Blanche, who was ransacking a box close by, full of cheap Valenciennes, ‘we might take some of this for pillow-cases.’

Madame de Boves did not reply and her daughter on turning her flabby face saw her, with her hands plunged amidst the lace, slipping some Alençon flounces up the sleeve of her mantle. Blanche did not appear surprised, however, but moved forward instinctively to conceal her mother, when Jouve suddenly stood before them. He leant over, and politely murmured in the countess’s ear,

‘Have the kindness to follow me, madame.’

For a moment she revolted: ‘But what for, sir?’

‘Have the kindness to follow me, madame,’ repeated the inspector, without raising his voice.

With her face full of anguish, she threw a rapid glance around her. Then all at once she resigned herself, resumed her haughty bearing, and walked away by his side like a queen who deigns to accept the services of an aide-de-camp. Not one of the many customers had observed the scene, and Deloche, on turning to the counter, looked at her as she was walked off, his mouth wide open with astonishment. What! that one as well! that noble-looking lady! Really it was time to have them all searched! And Blanche, who was left free, followed her mother at a distance, lingering amidst the sea of faces, livid, and hesitating between the duty of not deserting her mother and the terror of being detained with her. At last she saw her enter Bourdoncle’s office, and then contented herself with walking about near the door. Bourdoncle, whom Mouret had just got rid of, happened to be there. As a rule, he dealt with robberies of this sort when committed by persons of distinction. Jouve had long been watching this lady, and had informed him of it, so that he was not astonished when the inspector briefly explained the matter to him; in fact, such extraordinary cases passed through his hands that he declared woman to be capable of anything, once the passion for finery had seized upon her. As he was aware of Mouret’s acquaintance with the thief, he treated her with the utmost politeness.

‘We excuse these moments of weakness, madame,’ said he. ‘But pray consider the consequences of such a thing. Suppose some one else had seen you slip this lace –’

But she interrupted him in great indignation. She a thief! What did he take her for? She was the Countess de Boves, her husband, Inspector-General of the State Studs, was received at Court.

‘I know it, I know it, madame,’ repeated Bourdoncle, quietly. ‘I have the honour of knowing you. In the first place, will you kindly give up the lace you have on you?’

But, not allowing him to say another word she again protested, handsome in her violence, even shedding tears like some great lady vilely and wrongfully accused. Any one else but he would have been shaken and have feared some deplorable mistake, for she threatened to go to law to avenge such an insult.

‘Take care, sir, my husband will certainly appeal to the Minister.’

‘Come, you are not more reasonable than the others,’ declared Bourdoncle, losing patience. ‘We must search you.’

Still she did not yield, but with superb assurance, declared: ‘Very good, search me. But I warn you, you are risking your house.’

Jouve went to fetch two saleswomen from the corset department. When he returned, he informed Bourdoncle that the lady’s daughter, left at liberty, had not quitted the doorway, and asked if she also should be detained, although he had not seen her take anything. The manager, however, who always did things in a fitting way, decided that she should not be brought in, in order not to cause her mother to blush before her. The two men retired into a neighbouring room, whilst the saleswomen searched the countess. Besides the twelve yards of Alençon point at a thousand francs the yard concealed in her sleeve, they found upon her a handkerchief, a fan, and a cravat, making a total of about fourteen thousand francs’ worth of lace. She had been stealing like this for the last year, ravaged by a furious, irresistible passion for dress. These fits got worse, growing daily, sweeping away all the reasonings of prudence; and the enjoyment she felt in the indulgence of them was the more violent from the fact that she was risking before the eyes of a crowd her name, her pride, and her husband’s high position. Now that the latter allowed her to empty his drawers, she stole although she had her pockets full of money, she stole for the mere pleasure of stealing, goaded on by desire, urged on by the species of kleptomania which her unsatisfied luxurious tastes had formerly developed in her at sight of the vast brutal temptations of the big shops.

‘It’s a trap,’ cried she, when Bourdoncle and Jouve came in. ‘This lace was placed on me, I swear it before Heaven.’

She was now shedding tears of rage, and fell on a chair, suffocating. Bourdoncle sent the saleswomen away and resumed, with his quiet air: ‘We are quite willing, madame, to hush up this painful affair for the sake of your family. But you must first sign a paper thus worded: ‘I have stolen some lace from The Ladies’ Paradise,’ followed by particulars of the lace, and the date. However, I shall be happy to return you this document whenever you like to bring me a sum of two thousand francs for the poor.’

She again rose and declared in a fresh outburst: ‘I’ll never sign that, I’d rather die.’

‘You won’t die, madame; but I warn you that I shall shortly send for the police.’

Then followed a frightful scene. She insulted him, she stammered that it was cowardly for a man to torture a woman in that way. Her Juno-like beauty, her tall majestic person was distorted by vulgar rage. Then she tried to soften him and Jouve, entreating them in the name of their mothers, and speaking of dragging herself at their feet. And as they, however, remained quite unmoved, hardened by custom, she all at once sat down and began to write with a trembling hand. The pen sputtered; the words ‘I have stolen,’ madly, wildly written, went almost through the thin paper, whilst she repeated in a choking voice: ‘There, sir, there. I yield to force.’

Bourdoncle took the paper, carefully folded it, and put it in a drawer, saying: ‘You see it’s in company; for ladies, after talking of dying rather than signing, generally forget to come and redeem these billets doux of theirs. However, I hold it at your disposal. You’ll be able to judge whether it’s worth two thousand francs.’

But now that she had paid the forfeit she became as arrogant as ever. ‘I can go now?’ she asked, in a sharp tone.

Bourdoncle was already occupied with other business. On Jouve’s report, he decided on the dismissal of Deloche, a stupid fellow, who was always being robbed and who never had any authority over customers. Madame de Boves repeated her question, and as they dismissed her with an affirmative nod, she enveloped both of them in a murderous glance. Of the flood of insulting words that she kept back, one melodramatic cry escaped her lips. ‘Wretches!’ said she, banging the door after her.

[…]

And Mouret still continued to watch his nation of women, amidst the shimmering blaze. Their black shadows stood out vigorously against the pale backgrounds. Long eddies would now and again part the crowd; the fever of the day’s great sale swept past like a frenzy through the disorderly, billowy sea of heads. People were beginning to leave; pillaged stuffs encumbered all the counters, and gold was chinking in the tills whilst the customers went off, their purses emptied, and their heads turned by the wealth of luxury amidst which they had been wandering all day. It was he who possessed them thus, who held them at his mercy by his continuous displays of novelties, his reductions of prices, and his ‘returns,’ his gallantry, puffery, and advertisements. He had conquered even the mothers, he reigned over all with the brutality of a despot, whose caprices ruined many a household. His creation was a sort of new religion; the churches, gradually deserted by wavering faith, were replaced by his bazaar, in the minds of the idle women of Paris. Woman now came and spent her leisure time in his establishment, those shivering anxious hours which she had formerly passed in churches: a necessary consumption of nervous passion, an ever renewed struggle of the god of dress against the husband, an ever renewed worship of the body with the promise of future divine beauty. If he had closed his doors, there would have been a rising in the street, the despairing cry of worshippers deprived of their confessional and altar! In their still growing passion for luxury, he saw them, notwithstanding the lateness of the hour yet obstinately lingering in the huge iron building, on the suspended staircases and flying bridges.

Émile Zola originally published The Ladies Paradise in 1883. The translation from which this excerpt is taken was completed by Ernest Alfred Vizetelly in 1886.