DRIES VAN NOTEN SPEAKS with care and reserve, like someone well aware of his privileged position in the fashion industry. In Dries’ case this is a standing that has been deftly and meticulously carved over the years, a feat which, in the eyes of many, makes it even more well deserved. For someone who started designing under his own name when few in the business envisioned that fashion could come from Antwerp, let alone pronounce Belgian brand names, the success and rave reviews that Dries is currently enjoying have been a long time coming. Today he is one of the few remaining independent designers, an accomplishment that makes his brand somewhat of an anomaly in the contemporary fashion industry. Nevertheless, Dries, as the designer himself coyly intimates, has to start thinking about his future. Could it be that another of the enduring bastions of fashion sovereignty is about to end up in the hands of a business conglomerate?

Anja: In an interview you once said that ‘The good thing about fashion is that you always go ahead, the next, the next, the next – you don’t have time to look back’. Why is it good not to look back?

Dries: It is good to look back, but I don’t want to be nostalgic. I don’t see the point of dressing up in clothes from the past; there’s a reason why fashion changes with the times.

Anja: But nostalgia seems to have become a very important element

in contemporary fashion – why is that do you think?

Dries: People think that things were easier or more pleasant in the past, but that’s not the case. My team and I often have discussions about this. It’s interesting because I’m an older guy now and they are all very young. When we talk about the 1970s for instance, they think about ABBA as one of the icons of the decade. They don’t know that ABBA at the time was considered to be extremely bad taste – vulgar and completely unfashionable. ABBA was still wearing platform shoes when everyone else had already moved on. What I mean to say is that it’s not always the best versions of the past that live on.

Anja: How do you negotiate the conflict between, as you’ve been known to say, there being too much fashion in the world and at the same time, having always to produce more to stay in business?

Dries: I wouldn’t say that I’m completely at peace with this, but I don’t think of my clothes as just more products in the world. I try to do an honest job and make things that have a reason for existing other than just making money. I want to make clothes that allow wearers to communicate something about their personality. Of course I also have to compromise and make basic T-shirts to survive sometimes. But overall, I put my heart in everything I do. I can only hope that this makes my work worthwhile.

Anja: Do you ever have doubts?

Dries: Everyday. I never stop questioning what I do. Before a fashion show I might get nervous and start thinking, ‘Maybe we should have chosen different music, or maybe those shoes aren’t quite right’. But at the same time, if you’re perfectly sure of everything you do, then what’s the point?

Anja: What is success to you?

Dries: Success and happiness are intertwined. To me success is not about scoring, as it is to a lot of people. It’s about feeling good about things, it’s about living a good life.

Anja: How do you apply that principle to how you do business?

Dries: I try to do business in the same way. Had we wanted to, we could have had a store in every major city in the world, but that sort of success was never for me. When we open a store I want it to be in a nice location, I want the staff to be people I like. The most important thing to me is that my work is creative. I want to put all my energy and enthusiasm into colours, fabrics – things like that. I don’t automatically think about whether it will sell well or if I’ll earn a lot of money.

Anja: Is this a strategy that you’ve deliberately followed throughout your career?

Dries: I wouldn’t say it’s ever been deliberate. When I started in the mid-Eighties it became clear pretty quickly that to be a Belgian fashion designer was seen as an anomaly. The other designers from Antwerp that I started out with, well, we realised that we wouldn’t fit easily into the system. We had to find our own way. We had no money, so working together made us stronger but forming a group was never a marketing idea. It was just that people couldn’t pronounce our names so we became ‘The Antwerp Six’. I didn’t set out to be different though, it all happened very organically.

Anja: How do you feel you have changed as a designer over the years?

Dries: I hope that getting older and more experienced has made me wiser. I don’t want to ever fall back on formulas – that’s the worst trap for a fashion designer that’s been in the business a long time. You know, when you follow a tried and tested recipe that dictates adding a little bit of this, a pinch of that, shaking it and hey presto – there’s the new collection. I want to surprise and I want to stimulate creativity in my team – that to me is very important.

Anja: How do you ensure that you don’t fall into the trap?

Dries: The research process is incredibly important. Every season I start afresh – I want us to begin with a blank page, even if where we end up is not far from the last collection. To feel creatively stimulated I need to go through the whole research process – I couldn’t just pick up from where we left off last season. That’s why we aren’t yet part of a big conglomerate. I want to be able to make my own choices.

Anja: Not yet, you say?

Dries: Well, you never know what’s going to happen in the future… I’m fifty-six now, I don’t know what the situation will be like when I’m sixty-five. Maybe I’ll want to stop. But the fact is that I’m responsible for my team and all the people who have invested in us; all the people that work in production are dependent on me. Maybe when that time comes, the best thing to do is to take a partner or to sell the company. I don’t know. But I do know that I’m not going to do this forever – I’m not Armani.

Anja: Why is it important to you that the company remains even if you’re no longer involved?

Dries: It’s not that it’s important for its own sake, but of course it’s nice to know that what I have built will live on. It’s not that I’m looking to leave anytime soon, I love what I do. But I have to start thinking of the future, because I don’t have eternal life. We have to consider our options. In Antwerp we have over a hundred people working for us and in India there’s a few thousand people just working on our embroidery. It would be a pity to just suddenly say, ‘Okay, that was it – bye!’

Anja: Do you worry that your legacy might be misinterpreted, were you to leave it in the hands of somebody else?

Dries: I can pass on my message to the people who continue when I’m no longer here, but I can’t control what happens of course. If I step out, I step out and I have to assume responsibility for my choice. And I still have enough things to do in life that, once that day comes, I won’t always be looking over my shoulder to see what’s happening with the company.

Anja: You often seem to be represented as an outsider to the fashion system:

no advertising, no pre-collections, based in Antwerp, independently owned – do you see yourself as an outsider?

Dries: No, because it was never something I set out to become. Every decision we made was based on our circumstances at the time, and my position in the industry is a result of that. It’s all happened very organically. I lived in Antwerp when I started, rent is cheap here. We found an incredible building so why move to Paris? The same logic applied when we found our shop in Paris. My intention wasn’t to set myself apart from the well-established shopping districts, it’s just that we found a shop that I really loved with an amazing view over the Seine.

Anja: How do you see your own role in the behemoth that the fashion industry today has become?

Dries: I don’t know. We’re not the only ones who work in a different way. There are others. But my decision not to make pre-collections like all the major brands do for example, is based on the fact that we wouldn’t have the time to make it as well as our main collection. My team is not big enough. Also, I want to see every yarn, every palette, every button – every element of every collection. That, to me, is the fun part. I don’t like meetings; I like to be hands-on in the creation. But really, we just do the best we can with what we have.

Anja: Are there parts of the fashion industry that you find hard to identify with?

Dries: Actually, I think that the good thing about the fashion industry today is that it allows for a lot of different alternatives. In the Eighties and Nineties there was just one way. In the late 1990s when the big groups started buying up independent designers, it looked for a while as if that was the future – we all had to become part of a big conglomerate. We also considered it seriously for a while. But we didn’t make that leap, it wasn’t for us – or not yet anyway. Instead we just kept working and with time people have come to respect that. Today, difference is celebrated. It’s the same with fashion itself. You can be dressed in Versace or in Yohji Yamamoto and be equally fashionable. There’s a lot more space for individuality today.

Anja: How do you feel about the pace of the fashion system – is there any way to circumvent it?

Dries: I’m lucky in that it doesn’t affect me too much. I get by without the pre-collections that are so essential for many other brands. When pre-collections started to become important, we felt the pressure to make them too of course. But we stuck it out, and today buyers seem grateful that we don’t make any. They spend so much time running around the world buying new collections that they complain about not knowing which season is which anymore. I think they appreciate a little time off.

Anja: I’m surprised to hear you say that. I’ve spoken to so many designers

who seem to feel that making pre-collections is an absolute requirement these days. How can you survive without it when so many others seem to think they can’t?

Dries: Well, for most designers the pre-collection is their commercial collection – it’s what they sell. Then they make a ‘fashion show collection’ that is useful in terms of image and gets them attention in the press. The equation, in terms of sales, is usually 75% pre-collection and 25% fashion show collection. The fashion show collection for most designers arrives late in the sales season, but we do it differently. We invite buyers to see us in Antwerp one month before we show it to press in Paris. This means that we can get early orders, which in turn helps us when we place fabric orders with our suppliers. If a fabric won’t arrive on time, we can let our buyers know and they can choose something else instead. All in all, this means that we can deliver a big part of our collection nearly at the same time when others deliver their pre-collections. to make pre-collections like all the major brands do for example, is based on the fact that we wouldn’t have the time to make it as well as our main collection. My team is not big enough. Also, I want to see every yarn, every palette, every button – every element of every collection. That, to me, is the fun part. I don’t like meetings; I like to be hands-on in the creation. But really, we just do the best we can with what we have.

Anja: This pace that you’re describing owes a lot to fast fashion, doesn’t it? It’s as if the fast turn-around that customers have come to expect from the stores on the high street, has also ended up completely altering the way high fashion brands work.

Dries: That’s true. You have to remember that in the past sell-through at department stores was assessed every six months; now it’s done every month. Department stores look at a designer’s monthly turnover per square foot now, so of course if you always deliver new products you’ll have a much more even sell-through. A brand like ours by contrast has a very high turnover for the first three months after a new collection arrives in stores, but that will be followed by two months of slow sales.

Anja: But seeing as you’ve been in business for over three decades by now you’ve also had a chance to build long-lasting relationships with buyers. Would it be fair to say that, as a designer who is very well established and well respected by now, certain allowances are made for you?

Dries: You have a point, but the fact is that my collections sell well. I don’t want to come across as a commercial designer, but I am a designer concerned with creating garments for men and women that sell. Other designers are concerned with creating an image so that they can sell accessories or perfume. In most companies, accessories, shoes and bags make up 60–70% of sales – for us it’s only 7%, the other 93% is clothing.

Anja: You have been stressing the importance of designing garments to wear, rather than garments for show, but how do you keep this balance in an environment that now puts so much emphasis on the photogenic nature of clothes?

Dries: I have had to start thinking about what garments look good viewed on an iPod or smartphone. The first three looks have to be intriguing enough to make people want to see the rest. You can’t tell the whole story at once.

Anja: On a slightly different note, what’s important to you in terms of ideology and design ethics?

Dries: The fashion industry is full of tricks about how to create desirability and make things more commercial. You can find it in how you merchandise a collection, how you link garments or how you connect an element that sold well one season to items the following season. I try to avoid all that. I want my work to be honest and straightforward – I don’t like tricks.

This article was originally published in Vestoj On Fashion and Slowness.

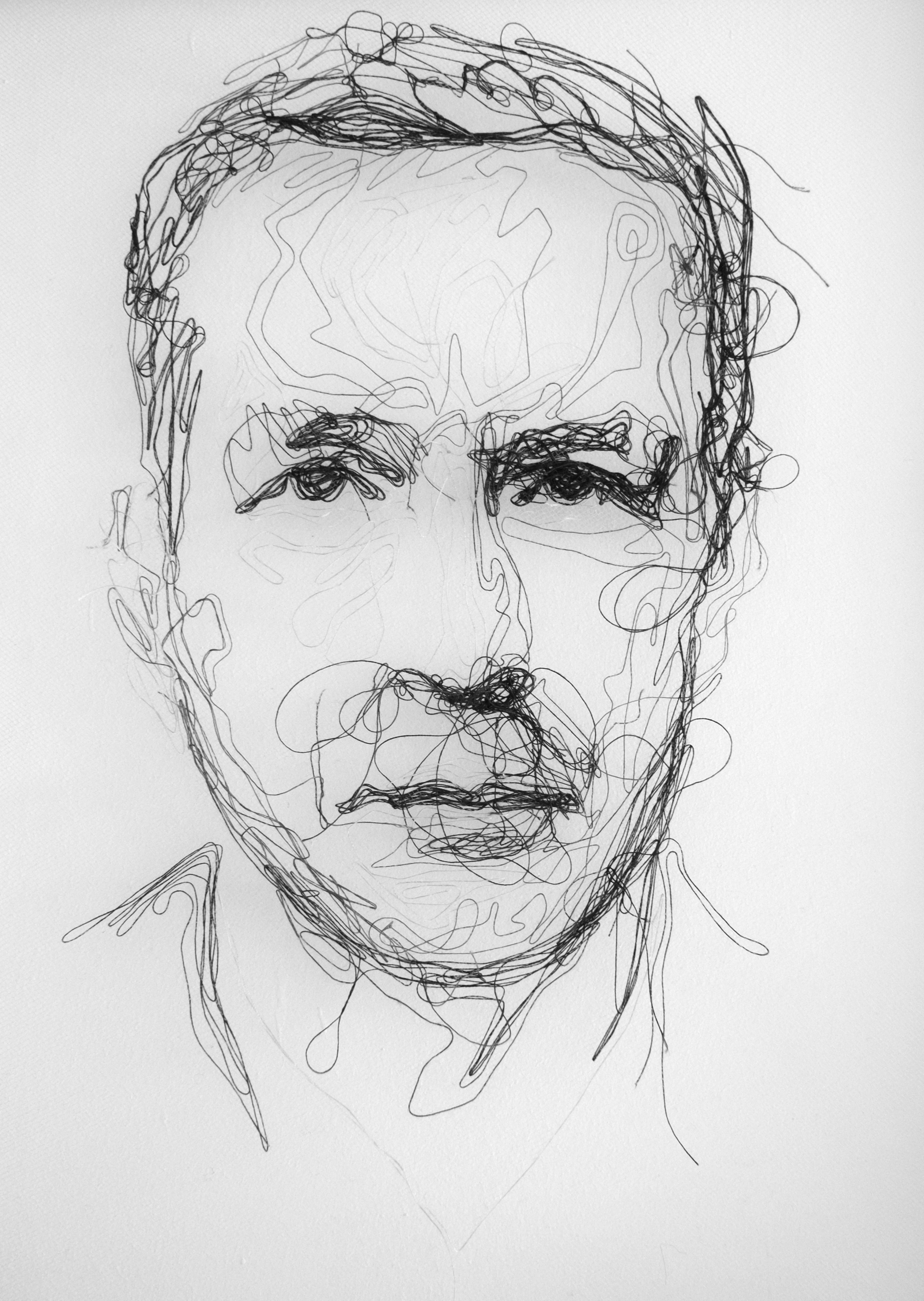

Louise Riley is a London-based textile artist and illustrator.

Anja Aronowsky Cronberg is Vestoj‘s Editor-in-Chief and Publisher.