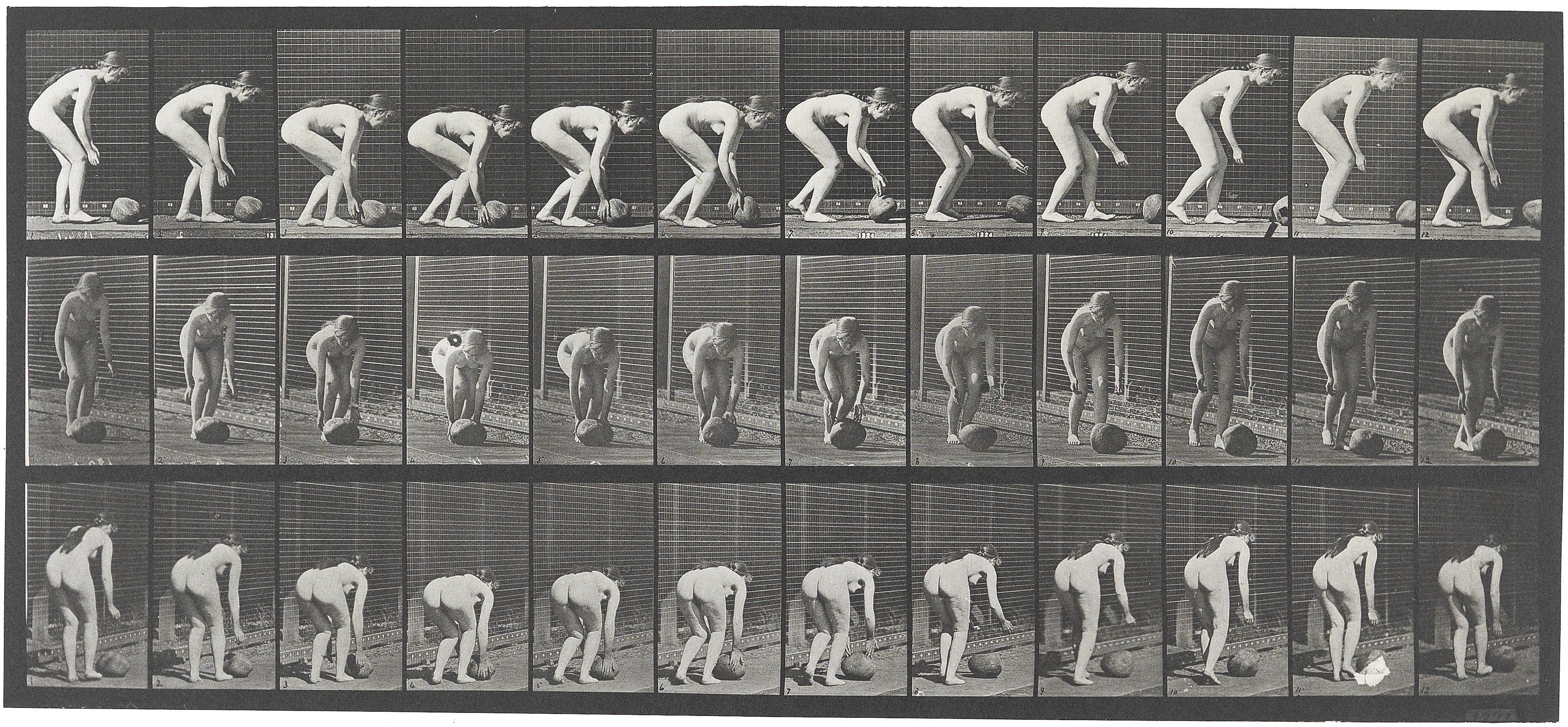

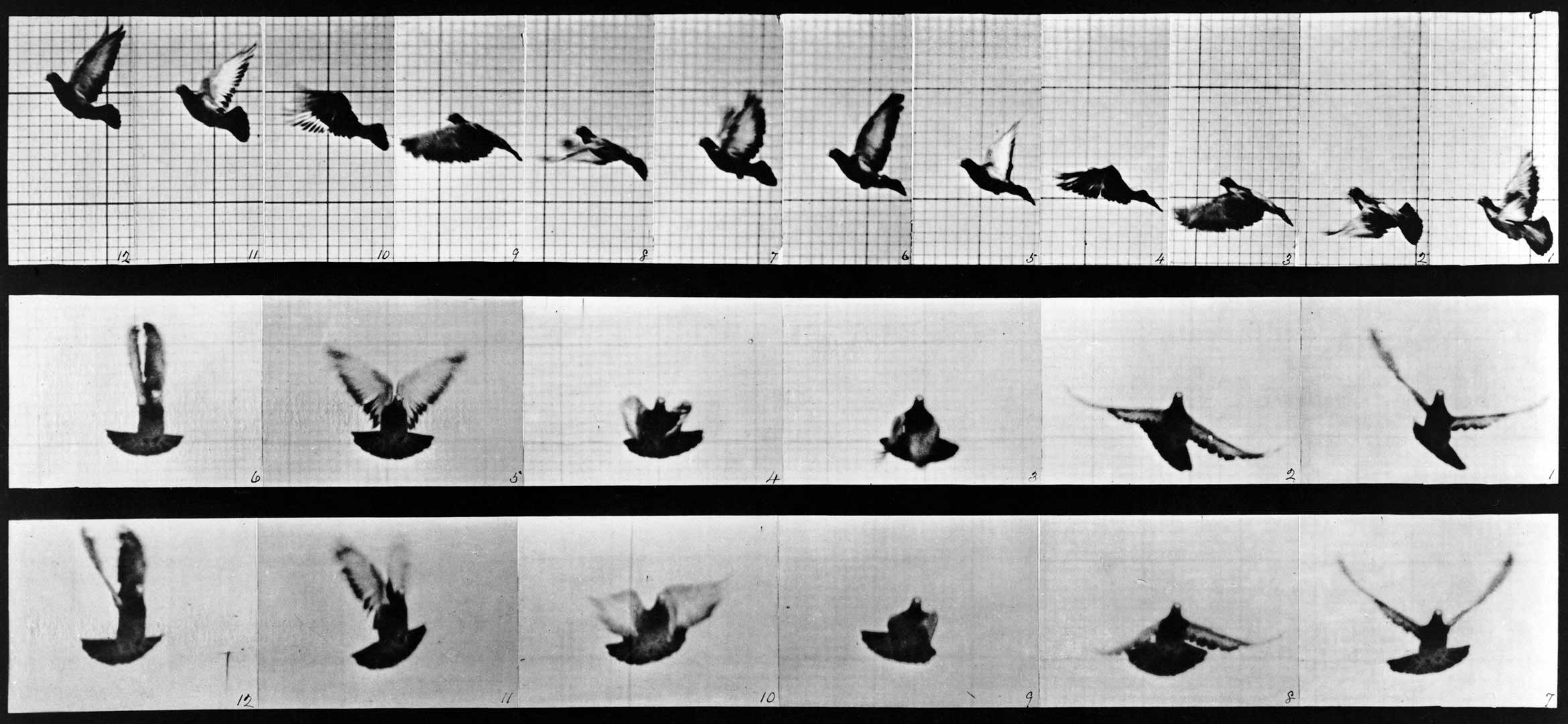

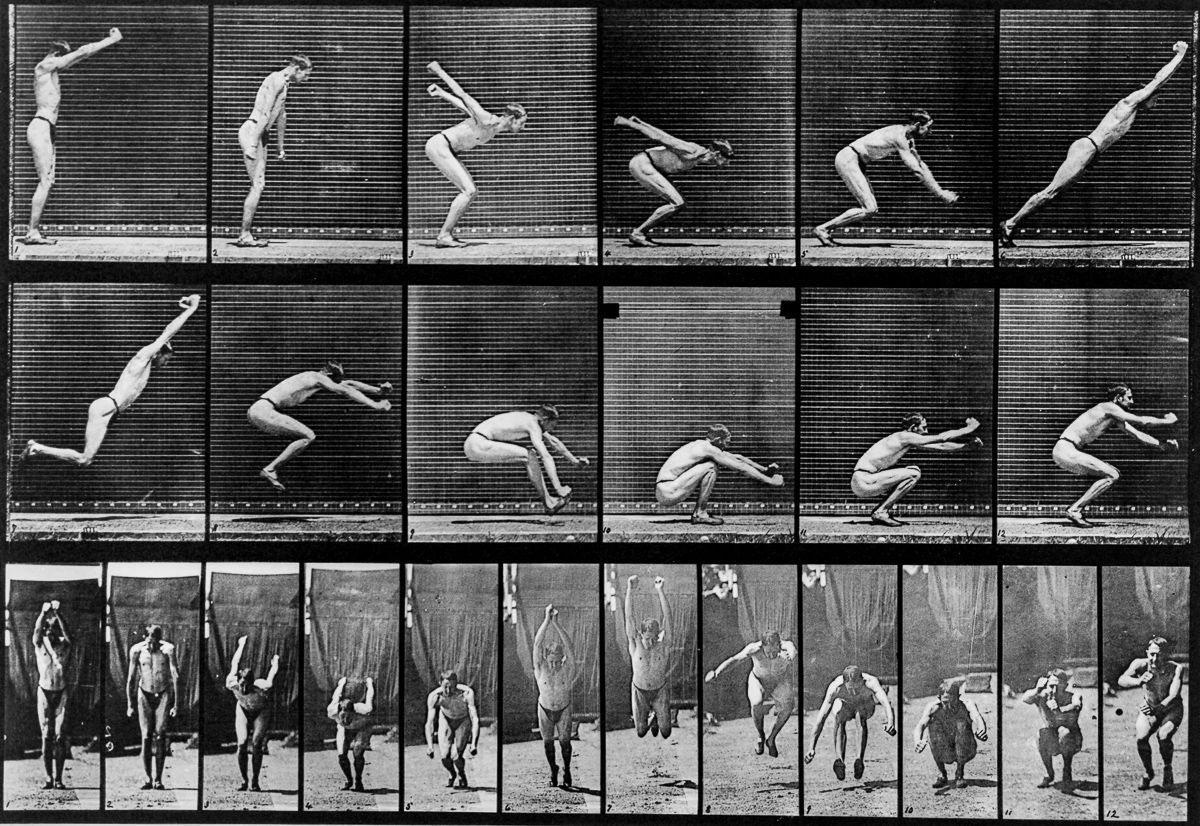

THE MANNEQUIN’S SIGNATURE POSE emerged somewhere between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the early twentieth century. Though the model’s walk appeared suddenly, her pose developed slowly throughout the decades, evolving from an upright and restrained pause to, by the 1920s, what became a relaxed gesture characterised by fluidity: her hips were forward, her shoulders back – her hands on her hips as she confronts the audience’s gaze. The early shows were trade events, kept out of the public eye. In these private functions, pragmatically, the poses served a very concrete purpose. Encountering the buyer, the frozen pose helped visualise the clothes, exhibiting its features and functions: she pauses and her athletic gesture demonstrates the elasticity of the jersey material.1 Frozen in time for even a split second, the gesture marked a break in the fluid walk of the mannequin, permitting her to be captured and crystallised within a still image, either by illustration or photograph, but most importantly as a fashion plate for the buyer’s gaze in an otherwise ephemeral environment.

But there was more to the mannequin’s pose beyond mere pragmatics. Fashion scholar Caroline Evans asserts that the mannequin’s pose was essentially a modernist phenomenon2 , arising alongside the modernist problem of representation – one that coincided with the rise of cinema.3 In an abstract sense, in Evans’ view, the pose imbued the garment, an essentially static object, with the motions of its wearer, thereby facilitating a dialectic between motion and stasis. By pausing to pose, the model allowed the garment to be captured as a fashion plate; but by gesturing the pose, the fashion plate came to reflect the entire flow of the mannequin’s walk, capturing her like a definitive singular frame in the moving image of film.

If the fashion show and pose are essentially historic, tied to the modernist movement of the twentieth century, then maybe the erasure of the fashion poses from the runway in our own time reflects the cultural trends of the twenty-first century. Today’s catwalk models no longer pose. And what use is the mannequin’s pose in this age of livestreaming and Instagram, when the preservative nature of modern media has expunged the transient nature of the event altogether? Weaving up and down the runway, models today become wholly defined by their motion. The rise of digital has undone both the concrete and abstract necessity of the gesture altogether. And this motion—on the catwalk and of the constant circulation of its images—feeds the fashion cycle, itself increasingly dependent on speed.

According to film scholar Stella Bruzzi, the couturier Elsa Schiaparelli once said that ‘what Hollywood did today, fashion would do tomorrow.’4 While she may have been referring to the realm of aesthetics, there is another way in which this adage rings true. In October of 2009 during Paris Fashion Week, Alexander McQueen staged his final catwalk presentation, sending models down the runway adorned in a digital alien print. With hairstyles approximating fins and sleeves pleated to resemble gills, McQueen’s amphibious mannequins paraded down the stage in a puzzling route, wearing pincer-like heels that distorted the flow of their walk. In partnership with Nick Knight’s SHOWstudio,5 a pair of gargantuan and predatory motion-controlled cameras affixed to rails spun up and down alongside the models, capturing their every move. Inspired by a catastrophic flood that engulfs the world, ‘Plato’s Atlantis’ invites us into a post-apocalyptic land of fantasy. The ‘us’ here is literal; for the first time ever, the Internet opened up access to the prestigious event to anyone with a broadband connection powerful enough to stream it.

In more ways than one, stasis is wholly excised from ‘Plato’s Atlantis.’ The swivelling cameras render the gesture of posing pragmatically redundant. The advanced tracking cameras subvert the audience’s gaze: there is no longer a single position of visibility and nothing needs to be visualised; the model no longer has to pause to demonstrate the elasticity of her dress: the cameras apprehend the contraction of every muscle, and with each contraction, the motion of the garment as well. With the advent of video-capturing technology, no time-slice of the model’s motion can escape us.

Though stasis survives, it appears to have been relegated to a lesser tier, condemned as something to be abandoned when possible. This subservience of the static to the moving is best exemplified by the implicit contempt that today’s designers – particularly younger ones – have towards traditional presentations, a format of demonstration where the garments are posed and shot much like how Evans describe a century ago. Initiatives like Fashion East in London champion emerging designers by offering them a chance to stage a fully produced runway show, allowing them to bypass the presentation format altogether. And for those who are relegated to presentations, many are choosing to incorporate the catwalk in them. This past London Fashion Week Men’s, Chalayan’s menswear ‘presentation’ was but an intimate catwalk show for various groups of press and buyers, looped in intervals through the afternoon like a video found on one’s social media feed. Emerging British designer Samuel Ross, meanwhile, made his fashion week debut for his label A-Cold-Wall this men’s week with an impromptu catwalk show incorporated into the presentation.6

The modernist paradox was this: how ought we represent the entirety of the model’s motions in a singular still image? Perhaps we can’t. But a characteristic of fashion in our time is that maybe we don’t have to. Not only do livestreaming and advanced camerawork allow us to extend the fashion plate in time through video, the fashion show has, in the last century and a half, evolved to become a public spectacle, particularly in the last few years through the rise of Instagram. This democratisation of fashion as image consumption comes at the price of the omnipresent nature of the singular fashion plate. Alongside the ubiquitous ‘Vogue Runway’ images are a slew of fragmented audience-produced runway images from all different angles, by the distinct individuals. Clicking on the geotag of the venue on Instagram after a show to reveals the same model and garments from a variety of angles. We as the audience are image-consumers, but we’ve also become image-producers.

But even this democracy of fashion remains a superficial one. Indeed, social media instils upon all of us a power to create; yet not all images are created equal. Power seems to be transferred from one institution to another, in an act of vertical dissemination and not horizontal. Editors give way to bloggers, while designers bend at the will of retailers. Rarely, if ever, is power assumed by the masses.

By now, any complaints of the pace of the fashion cycle probably seem a little platitudinous. Still, it’s worth taking a macroscopic view of the issue with the above in mind. Whereas the great private trade shows of the early twentieth century coincided with the paradoxical task of presenting motion through the motionless, the erasure of the static in our livestreamed public spectacles coincides with their own problem worth addressing. While our twentieth century counterparts confronted their own paradox, today, we’ve become concerned with ours: the conundrum of satisfying fashion’s consumers when, in Sisyphean fashion, that very fulfilment meant the introduction of a newer desire. From our twenty-first century perspective, immediacy has become the status quo. A several-month-long lag between image consumption and object consumption seems to be, by common standards, a broken affair: to instil upon the consumer a desire that will remain impossible to satisfy until the next season seems to be, as the argument goes, a counterintuitive way of conducting business.

In September 2016, when Burberry finally debuted its ‘see now, buy now’ collection at Makers House during London Fashion Week, in the eyes of many, the event marked the commencement of some strange new era. In a sense, those critics were perhaps right. For Burberry, the conventional cycle was no more. Its supply chain has fallen in tandem with the design process, yielding a congruity qua compression.7 With the traditional collection namesakes ‘Autumn/Winter’ and ‘Spring/Summer’ replaced by the unassuming and seasonless ‘September’ and ‘February’, for the first time in the brand’s history, the consumer’s delayed gratification of the past can now be displaced by the immediate indulgence of today.

To conflate cause and effect would be naïve. The removal of the fashion pose is not responsible for the acceleration of the fashion cycle; rather, it’s indicative of a greater conundrum. The same tools that have obliterated our previous problem carry their own. The modern fashion show, devoid of stasis and superficially democratised raises a question of sustainability. But as Nick Knight’s Tom Ford’s Spring/Summer 16 presentation8 – a wholly digital experience meant to be consumed in lieu of the show – suggests, if the fashion show as we know it is essentially a modernist phenomenon that embodies a dialectic between stasis and motion, one can’t help but question its purpose in our time when the static has become a rare occurrence altogether.

To deliberate slowness has become an act of protest. For Spring/Summer 15, to conclude the typical movement of the runway show, Dries Van Noten sent his group of models to the floor. The models planted themselves onto the ground, as the floral prints of their garments became rooted into the green grass. Reduced to flora, the models fell into stasis in opposition to the preceding event. But while Van Noten punctuates his show with stillness, one can’t help but feel an artificial unnaturalness that seeps through the whole thing. As the ultra-slow motion of the accompanying short film suggests, the slowness of the show is a statement in and of itself.9

Edwin Jiang is a writer in London.

C Evans, The Mechanical Smile: Modernism and the First Fashion Shows in France and America 1900-1929, New Haven: Yale UP, 2013. p 239 ↩

“[The mannequin’s] gestures and walk marked the time of modernity like a metronome: the fashion show staged not only modernist bodies but also modernist time, in which the flow of motion was punctuated by the pose.” ibid. p. 238 ↩

“All were concerned with the paradox of how to represent motion in still images at a time when film enabled, or was about to enable, the representation of moving images of the body; the pose is thus related to a ‘problem of representation being investigated in a number of parallel fields, which can be characterised as a ‘modernist enquiry” ibid. ↩

G Riello and P McNeil, The Fashion History Reader: Global Perspectives, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2010. p. 504 ↩

http://showstudio.com/project/platos_atlantis ↩

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1YRpzjUOAEk ↩

https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/intelligence/how-burberry-is-operationalising-see-now-buy-now ↩

http://showstudio.com/project/tom_ford_s_s_16 ↩

http://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/24967/1/relive-the-show-that-brought-fashion-week-to-a-standstill ↩