WHEN SEASON FOUR OF US drama series ‘American Horror Story’ began its run in October, the freak show re-entered the world of popular entertainment. While some would argue the format has never gone away,1 the scopophilic frisson of the American sideshow, coupled with the message that internal depravity rather than physical disability is the true marker of the ‘freak’ has largely been absent since Tod Browning’s ‘Freaks’ was filmed in 1932. The struggle between outward appearance and inner ‘beauty’ is a key aspect of the narrative of each, however displaying disability as ‘curiosity’ for entertainment is undeniably problematic both on the big and small screen.2

The fine line between beauty ideals and so-called ‘freak’ bodies is epitomised in the largely-forgotten freak show performer called the Circassian Beauty, who moved from a cultural trope used to sell cosmetics in the eighteenth century, to a sideshow act created by circus impresario PT Barnum in 1864. Theorist Robert Bodgan, in his seminal social history of the freak show, categorises the Circassian Beauty, along with sword-swallowers, snake-charmers and tattooed people as exotic self-made freaks – performers with fabricated stories that reflected the cultural concerns of the day.3 As current concerns about representations of disability are played out in American Horror Story, themes such as slavery and Orientalised eroticism were played out through the commodified body of the nineteenth century Circassian Beauty.

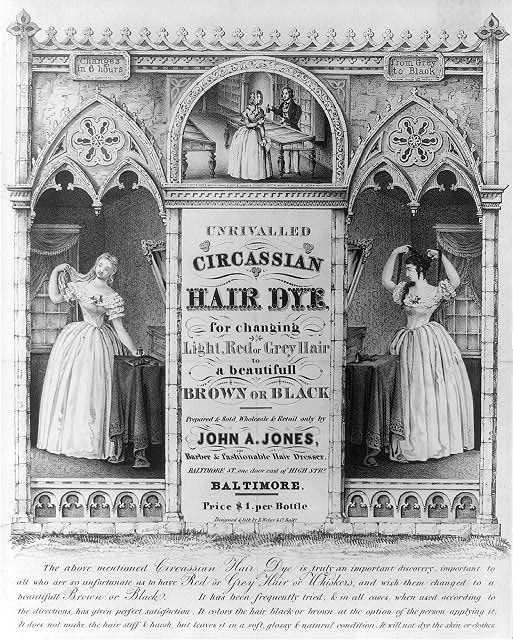

The image of the Circassian woman as a beauty ideal was developed by the racial taxonomies of physician and naturalist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in the latter half of the eighteenth century. Based on his research into skull shapes for his 1775 book On the Natural Variety of Mankind, he determined that all humans originated from the Caucasus region, and the women of Circassia were deemed the ‘purest’ and most beautiful in the world. Before long, the expanding cosmetics industry hijacked the Circassian ideal – with her dark lustrous hair, pale skin and rosy cheeks as a marketing ploy. George Crabbe, in his 1785 satire on journalism The Newspaper, illustrated this:

– Come, faded belles, who would your youth renew,

And learn the wonders of Olympian dew;

Restore the roses that begin to faint,

Nor think celestial washes vulgar paint;

Your former features, airs, and arts assume,Circassian virtues, with Circassian bloom.4

This plays on the product ‘Bloom of Circassia,’ a blusher that was advertised as providing the wearer with a long lasting ‘lively and animated bloom of the rural beauty’.5

The legendary beauty of Circassian women, became a key discourse during the Crimean War, when France, Britain and Sardinia supported the Ottoman Empire against the advances of Russia. The Illustrated London News wrote of the supremacy of the Circassian people in 1854, the year that Britain joined the conflict;

‘They are manifestly the true aristocrats of nature… Of the female type among the Circassians our Engravings furnish two or three specimens. The beauty of these women is, of course, well known – their too common destination is not worthy of this gallant and superior people.’6

Quote from the Illustrated London News, June 3, 1884.

The ‘too common destination’ referenced here refers to the Sultan’s harem where Circassian women were said to be especially prized for their beauty.

The notion of the harem has long been a site of Western Orientalist fantasy, epitomised by artists such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres who depicted it as an erotically-charged space, often laden with sapphic overtones. Circassian slaves in the Sultan’s harem also featured in Byron’s satirical epic poem Don Juan that he was still composing at the time of his death in 1824. The politics of the harem, however, operated with different conceptions of slavery to the transatlantic slave trade that Britain had outlawed in 1833. Governed by the laws of Islam, the harem slave system allowed both slaves and concubines certain rights, as well as opportunities for manumission, and was viewed as ‘consensual and a recognisable route to [social] advantage’.7 Western notions of slavery have been highly racialised, and the concept of white slavery was problematic in European and American minds.8

Despite these fears, slaves sold into harem life became an aspect of Western tourism when visiting Constantinople. The slave market became a key destination for tourists before it closed in 1847, and the wives of European ambassadors were often taken on harem tours where viewing slaves girls was part and parcel of the exotic display.9 The illicit thrill of the harem was as much a part of the spectacle for Western visitors in Victorian Constantinople as it would become in the freak shows of America, and combined the supposed despotism of the Ottoman Empire with the Orientalised sensual allure of the harem.

The Crimean War had shone a spotlight onto the beautiful Circassian slave in the Ottoman harem, and a decade later America found itself in the midst of a Civil War dominated by ideologies of enslavement and freedom. It was at this point that showman and future circus impresario PT Barnum stepped in, ever keen to capitalise on exotic tales of savagery and captivity, using the harem as the epitome of the Orientalist fantasy. From Barnum’s correspondence it becomes clear that accepted ideas about the Circassian ‘beautiful white slave girl’ were paramount in his decision to add them to his roster. He wrote in a letter to his procurer;

‘I still have faith in a beautiful Circassian girl if you can get one very beautiful […] or if you can hire one or two at reasonable prices, do so if you think they are pretty and will pass for Circassian slaves […] If you don’t find one that is beautiful & possesses a striking kind of beauty, why of course she won’t draw and you must give it up as a bad job.’10

With Barnum re-casting the Circassian Beauty for an American audience he was playing into contemporary debates that raged around freedom and slavery. His first Circassian Beauty, Zalumma Agra ‘the star of the east’, went on display in 1864 – during the Civil War – and became the prototype for an act that remained a feature of the sideshow for nearly fifty years.11

Barnum circulated a story that he sent one of his employees to find a Circassian slave for him to put on display, who only succeeded by disguising himself in Turkish garb and buying ‘Zalumma’ from the slave market, in order to save her from life in the harem. While this story suited the needs of Barnum as the consummate showman, a more realistic version is that a local girl with bushy hair came to the museum looking for work, and she subsequently became the first Circassian Beauty performer.12

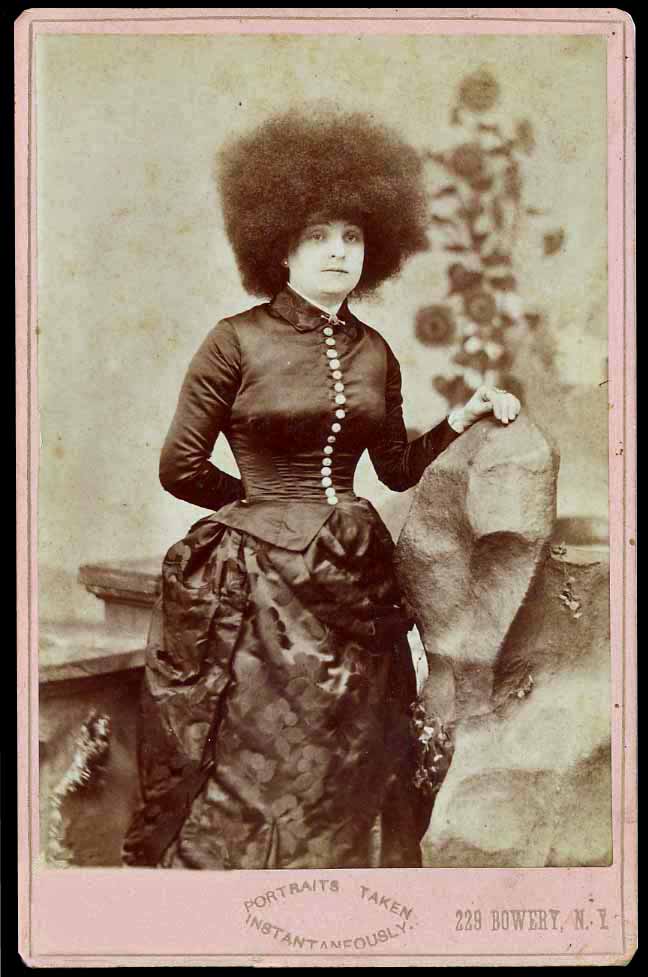

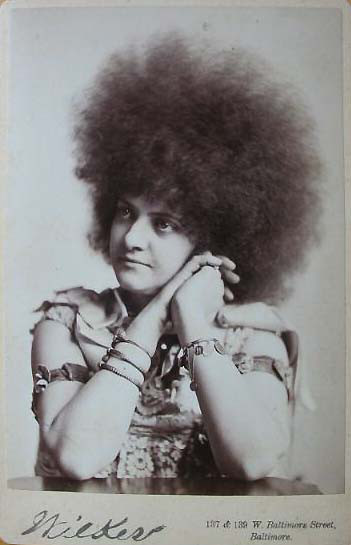

The tightly-curled hair of Barnum’s Circassian Beauty became a key attribute in the replica acts that followed. While the original reasons for the hair are unknown – and could have simply been a natural feature of the first performer – it’s difficult not to read it as the feature that turns the sideshow Circassian Beauty into a uniquely American character. The tight curls resembling Afro-textured hair, later achieved by soaking the hair in beer and teasing it into shape,13 were not reminiscent of either Circassian women or representations of the harem. Literary and Cultural scholar Linda Frost noted that the hair mimics so-called ‘primitive’ sideshow exhibits such as the Fiji Cannibals, and has also highlighted the mythic stereotype of the promiscuous sexuality of African-American women that was circulating in America at this time.14 Re-cast with Afro-textured hair, the Circassian Beauty represented white anxiety about miscegenation at a time when Civil War raged in an attempt to end slavery, adding a new layer of exoticised sexuality to a figure who now not only represented the Orientalised bondage of the harem, but also the ravenous sexual appetite of the African-American woman. For Barnum, there can be no doubt that sex and slavery sold well.

The Circassian Beauty was constructed by Barnum as an embodiment of the seductive qualities of the harem, and as such her garments was paramount. She wore baggy Turkish-style trousers with revealing flowing garments, ornate capes and ‘star of the East’ motifs.15 A popular prop on stage was a water pipe, and Robert Bogdan noted that a Turkish resident in New York was consulted over the initial Circassian Beauty’s dress and name.16 Sideshow postcards emphasised the exotic and erotic qualities of the performers, and studio shots accordingly featured items such as animal skins or palm leaves.17 Through the combination of her dress and hair, Barnum’s Circassian Beauty embodied a host of conflicting cultural signifiers, including, as Frost has pointed out, ‘notions of Colonial ambition and Orientalism, the superiority of the United States and Manifest Destiny, the position of women within Victorian America and the cult of True Womanhood, the purity of the white race and the sexualisation of the African-American woman’.18

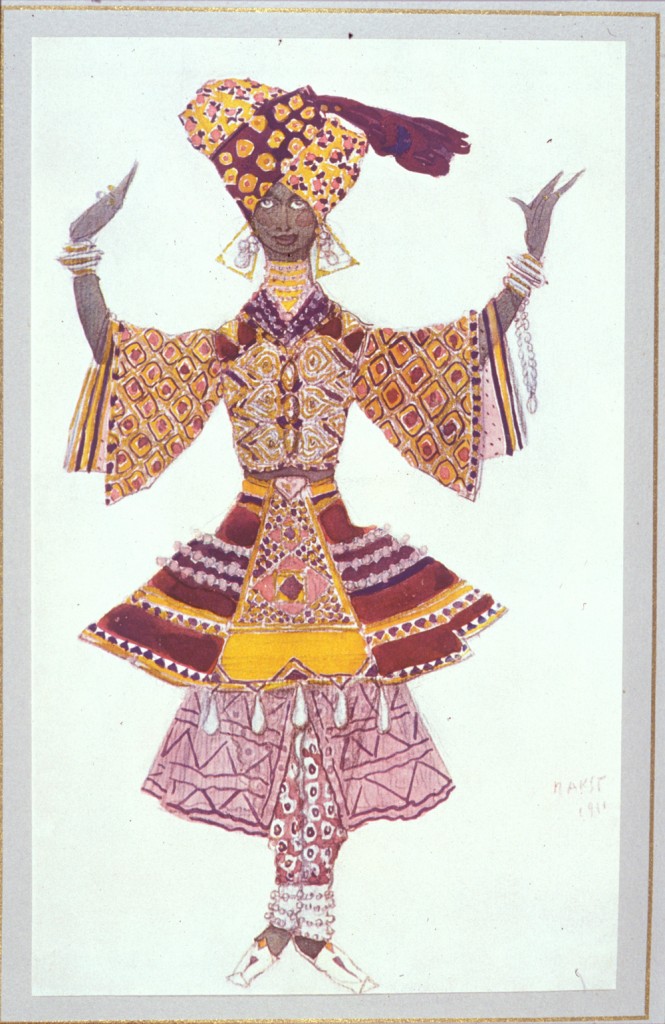

Cultural studies scholar Niall Richardson writes that the ‘freak’ is a cultural construct.19 As such it’s understandable that the Circassian Beauty as a freak show staple died out by 1910,20 as the harem slave trade had come to an end, leaving the character of the Circassian girl rescued from the Sultan’s harem somewhat redundant. However, the harem itself was ripe for revival in European Orientalist fantasy, and concurrent with the demise of the self-made Circassian Beauty in the American freak show was the rise of the harem in another form of entertainment – the opulent productions of the Ballets Russes and the spectacular fashions of Paul Poiret. Ballets Russes costume designer Leon Bakst created his first pieces for Cleopatra in 1909, followed by the success of Scheherazade in 1910, directly inspired by the Arabian Nights.

The Circassian woman went from a beauty ideal and advertising trope to an embodiment of racial fears surrounding slavery and a sideshow exhibit in a little under a century. The display of ‘raced’ bodies, contextualised within the history of freak shows, remains contentious from theatre to art exhibits and celebrity culture. Depictions of disability – frequently at the heart of the freak show – are again a subject of debate through American Horror Story, which in its carefully constructed colour palette and stylistic choices once again blurs the boundaries between fashion and ‘freak’, and questions our cultural ideals of the body beautiful.

Amber Butchart is a fashion historian and an Associate Lecturer at London College of Fashion.

See N Richardson, Transgressive Bodies: Representations in Film and Popular Culture, Ashgate Publishing Limited, Surrey, 2010 ↩

For more on these arguments, see Emily Nussbaum’s piece ‘The New Abnormal’ in the New Yorker, December 8th 2014 http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/12/08/new-abnormal ↩

R Bodgan, Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1990, p. 235 ↩

As cited in J Strachan, Advertising and Satirical Culture in the Romantic Period, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007, p. 110 ↩

Ibid, p. 208 ↩

Illustrated London News, June 3 1854, p533-534 ↩

R Lewis, Rethinking Orientalism: Women, Travel and the Ottoman Harem, IB Tauris, London, 2004, p. 130 ↩

Lewis (2004), p. 131-132 ↩

Lewis (2004), pp132-133 ↩

Cited in L Frost, ‘The Circassian Beauty and the Circassian Slave: Gender, Imperialism and American Popular Entertainment’ in Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body, R Garland Thomson (Ed.), NYU Press, New York, 1996, p. 248-249 ↩

This was an especially relevant year as the Russian conquest of the Caucasus was complete by 1864, leading to forced mass exile of the indigenous Circassian people, and sounding the death knell for the concept of the Circassian Beauty as a symbol of the white slave trade. This compulsory movement of peoples has been retrospectively labelled by some as genocide and ethnic cleansing. For more see W Richmond, The Circassian Genocide, Rutgers University Press, New Jersey, 2013 and R Does ‘The Ethnic-Political Arrangement of the Peoples of the Caucasus’ in F Companjen, L Károly Marácz and L Versteegh (Ed.), Exploring the Caucasus in the 21st Century: Essays on Culture, History and Politics in a Dynamic Context, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2010. ↩

Bogdan (1990), drawing on an unpublished account of a contemporary of Barnum’s, p238 ↩

Ibid p257 ↩

Frost (1996) p259 ↩

Frost (1996) p257, Bogdan (1990) p238 ↩

Bogdan (1990), p235, 238 ↩

Frost (1996) p257 ↩

Ibid p250 ↩

Richardson (2010) p5 ↩

Bodgan (1990) p240 ↩