We feared that Prato would be the most dangerous place in Italy after the outbreak of the novel coronavirus. Friends, relatives, and colleagues who knew about our ethnographic research with Chinese migrants in greater metropolitan Tuscany began reaching out with trepidation.

Prato hosts Europe’s largest concentration of Chinese migrants, who have become formidable entrepreneurs and workers in the globalised iteration of the prestigious Made in Italy fashion industry. Like many politicians, public health officials, and journalists, our hunches about Prato becoming a Covid-19 epicentre were based on common sense. But not all common sense is good sense. Our predictions couldn’t have been more wrong — a reminder that origin stories of diseases are distinct from their life histories, which also manifest in social narratives and practices. And although such histories can be useful for tracing contagion within societies, these histories can also be used for political purposes that may be as dangerous as the disease itself. In the case of Covid-19, knowledge related to its origin story has fed xenophobic sentiments that target Chinese migrants as well as individuals who ‘look’ Chinese. The origin story evolved — or, might we say, mutated — into its own narrative of blame. Such mutations call for intervention.

As it turns out, the threat of stigma, knowledge of quarantine, and the will of solidarity motivated an entire migrant community to take action — similar to Chinese migrants elsewhere in Italy and Europe. Some 25,000 migrants with Chinese citizenship reside officially in Prato, and estimates suggest about twice that number live there when undocumented migrants are included. Among them, only a single person in the entire Region of Tuscany has been diagnosed with novel coronavirus.

Of about 7,500 positive cases of Covid-19, Tuscany’s Regional Health Agency (ARS) has identified the national origin of 6,000 cases, of which 100 were ‘foreigners,’ primarily Albanian, and only one in the entire region was of Chinese nationality, according to Fabio Voller, the region’s ARS Coordinator of the Epidemiology Observatory.1 The Province of Prato has a relatively low level of overall infection (404 cases, or 16 per 10,000, in a population of 257,716 as of April 15).2

Many Chinese citizens had experienced their first quarantine in mainland China after travelling to Wenzhou in Zhejiang Province in early February to celebrate Chinese New Year. Upon their return to Prato, messages circulated via the WeChat social media app, tracking individual travel departures and arrivals between Italy and China, health status, and phone numbers so friends could pressure others to follow self-quarantine measures.

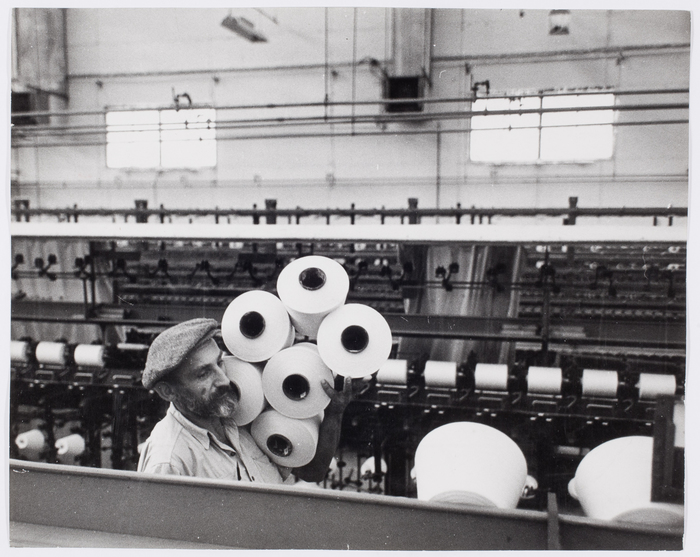

Meanwhile, stories of violent acts of xenophobia from cities to the North and South circulated among tight-knit families that make up Prato’s 6,000 Chinese-owned firms. More than half of those firms (3,700) are categorised as confezioni, or cut-and-sew workshops. Other Chinese firms include fast-fashion wholesalers, textile factories, and services that support those businesses and the people working in them, such as real estate activities, restaurants, bars, and small retail shops.3

Worry grew among members of the Chinese community — diverse in terms of socioeconomic class, education, as well as documented status — that such violence could spread to Prato. They sensed being in a vulnerable position to become victims of a major blame campaign. Some feared for their lives. They wondered if they would be targeted and pressured to leave the country. Being seen as the source of contagion could devastate their social well-being and threaten their businesses and economic livelihood. Thus, the second quarantine happened as Prato’s Chinese residents collectively put themselves into self-quarantine several weeks before the Italian government issued the nationwide stay-at-home order on March 9.

Overnight, typically crowded streets turned silent. Fast-fashion businesses ground to a halt. The Chinese-populated neighbourhood known as Macrolotto Zero transformed into a ghost town. Bars and retail stores emptied out as did grocery store shelves. Teachers noticed that Chinese students were absent, and assuming that the students were staying home for fear of being bullied, authorities pleaded with parents to send their children back to school.

Given Italy’s nationwide lockdown, some Chinese residents are thus in their third quarantine. The extent of distancing among the Chinese community is particularly noteworthy considering the Wenzhou ‘spiritual insistence’ related to hard work, manifesting in intense just-in-time rhythms of the fast-fashion niche, in the pursuit of making money to pay off debt and becoming your own boss.

We reached out to several public figures from the Chinese community in greater metropolitan Tuscany. Franca Hong, until recently active in a youth association and herself a young entrepreneur of an accessory firm on the outskirts of Florence, spoke of a widespread sense of civic responsibility. She emphasised that the more people adhere to the stay-at-home orders with a sense of discipline, the sooner the situation will pass. Noting that business was largely at a standstill, she pointed to the power of employees in small Chinese family-owned firms as having a crucial role over production given the productive model of the Chinese firms; she credited the workers with insisting on not coming to work but rather on quarantining. She underscored a collective sense of being ‘in the same boat’ as fashion makers and distributors shut down production and sales outlets. This, too, has strengthened a sense of solidarity. A silver lining in this period of pause has been to prompt people to reflect on life and to prioritise health and family.4

Marco Wong, elected to Prato’s city council in June 2019, identified guiding sentiments in three phases: fear of a formidable contagion stigma; solidarity against discrimination; and a desire to show goodwill through donations of medical masks and protective gear. He defined the first phase as deeply painful as people learned through social networks and word of mouth of troubling incidents of xenophobia. There was profound worry among the Chinese migrants in Prato that they would become victims of hostility. In turn, a second phase gave rise to sentiments of solidarity and actions of good will, including some workshops converting operations to the manufacture of masks. He characterised the third phase as Chinese being recognised as saviours of the patria, or the nation, as manifested through widespread gifting of essential items such as masks and other medical equipment.5

It’s worth pointing out that the migrant population is fairly young and less affected by the virus. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that, given the concentration of Chinese residents, Prato ended up being the last province in Italy to register persons affected with Covid-19. The city boasts the highest percentage of migrants anywhere in Italy. Of its total population of 195,089, some 42,371, or 22 percent, are classified as stranieri, or foreigners. (The national average is around 8.5 percent foreign residents.) Registered Chinese migrants yield numbers of around 58 percent of official resident foreigners.

The situation has profoundly shifted the image of Chinese migrants. Prato’s mayor, Matteo Biffoni, described his city as ‘in the eye of the hurricane’ and pointed to the Chinese citizens’ behaviours as ‘exemplary’ for leading the way to a circolo virtuoso, or a virtuous society. In an article published in the national newspaper La Repubblica, he underscored that the Chinese community had set a good example for Italians. It is no coincidence that Biffoni himself ran his electoral campaign against hate and, rather, on a platform of love.6 The behaviours among Chinese residents of Prato appears to have convinced others of the necessity to follow strategies aimed at limiting the risk of contagion; the effectiveness of such practices was also evident from reports of decreases in infections in China.

An unexpected consequence of Covid-19 has been a sea change: the very community that a New York Times article pointed the finger at to explain Italy’s racist roots and lurch to the populist right has gone from being a source of fear and resentment to being one of the most admired in Italy.7 ‘They’ve saved us,’ remarked Anna Ascolti, a psychologist friend who works in Prato’s public health agency.

Prato has been a laboratory of globalisation particularly related to fast fashion. Future prospects point to the city as different sort of laboratory. One blogger, Huang Miaomiao, who uses the hashtag ‘I am not a virus,’ #iononsonounvirus, envisioned this future as including dialogue, innovation, and mutual responsibility.8 Others underscore possibilities for diversifying the economy through new creative enterprises that build on the region’s fashion strength. Supply chains may be reimagined. Temporalities may shift or at least be questioned. New ways to realise sustainability for people and the planet may emerge.

As anthropologists who have collaborated during the past decade to understand the ways in which families, individuals, and institutions cope with globalisation, we want to emphasise that disease origin stories, while important, can lead to dangerous narratives. We need to recognise that the hegemony of global supply chains to produce the clothes that are advertised, stocked in retail outlets, bought and worn should not lead to ‘pathologising’ the entrepreneurs and workers who produce them. We need to imagine different futures that push back against demographic nationalism. We need not to criminalise the people who work hard to make clothes as they follow a desire to realise dignified lives. Diseases have not only origin stories and life history narratives but also afterlives. Social narratives related to coping with transmission and prevention practices also need to be tracked, understood, and respected.

Elizabeth L. ‘Betsy’ Krause is the author of Tight Knit: Global Families and the Social Life of Fast Fashion (University of Chicago Press, 2018) and professor of anthropology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Massimo Bressan is president of IRIS, a social and economic research institute in Prato, Italy.

Interview with subject, April 14, 2020. See also https://www.ars.toscana.it/images/qualita_cure/coronavirus/rapporti_Covid-19/Report_coronavirus_14_aprile_2020.pdf ↩

https://lab.gedidigital.it/gedi-visual/2020/coronavirus-i-contagi-in-italia/?ref=RHPPTP-BH-I251620115-C12-P2-S1.12-T1 ↩

interview with subject, March 31, 2020 ↩

Interview with subject, April 3, 2020 ↩

https://www.repubblica.it/dossier/politica/virus-in-comune-sindaci/2020/04/03/news/coronavirus_intervista_sindaco_prato_matteo_biffoni-253004431/?ref=search&fbclid=IwAR3RzeUWPPllgBPc2BzejyJAS-m3B88raH9oipiuaSfZVcjRvyAIwjz5v7I ↩

P S. Goodman and E Bubola. 2019. ‘The Chinese Roots of Italy’s Far-Right Rage,’ The New York Times,https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/05/business/italy-china-far-right.html ↩

https://www.huffingtonpost.it/entry/doppia-quarantena-cosi-i-20-mila-cinesi-di-prato-hanno-affrontato-il-virus_it_5e830158c5b6d38d98a4343d ↩