In 1992, a new family with five children moved into our street. Growing up with two brothers, I was excited to hear that there were two other girls in the household. Upon meeting them and surveying their rooms, I marvelled at their toy collections: they had all the Barbie stuff my dreams, but not my room, were made of: a pink mobile home, a convertible car, a Barbie house and several Barbie horses. One doll however, struck me as the most exotic, incredible and most beautiful creature: it was the 1992 Totally Hair Barbie, designed by Carol Spencer. She had a mini dress in fluorescent Pucci-style print, and her extremely long, floor-grazing locks were permanently crimped and came with hair gel. That day, I started a campaign with my parents to obtain a Totally Hair Barbie, even though up till then I’d only had a few basic dolls, one Skipper and many hand-me-down Barbies, since my green-party parents were not very enthusiastic about the American ‘teenage fashion model’ with pink plastic accoutrements. Once I got one, the best thing to do was go over to my neighbours’ house, where two of those dolls lived with the two girls, and add mine to their pair, so we could play with a Total Hair extravaganza set of three dolls, twisting the different strands and braid them together in a sort of octopus-like hair situation.

*

Carol Spencer: In those days, Pucci was all over the stores in the USA, and I mocked up the dress by glueing separate Pucci-print-shapes onto a small scale model, because it was right before the time when I learned to do this on the computer, and we made custom prints. At Mattel, we could not source fabrics with a print small and legible enough for the doll so the print fabric had to be created from scratch. I just came back from a time living as an expat in Hong Kong working for Mattel’s Design Studio (1988-92), and wanted to prove my seniority to the design team in LA. There was a rigorous process of approving designs, going through many different departments at the company, and I ‘sold’ the marketing department the idea of dressing Barbie as a sort of Eve in her long, crimped hair, with a short dress to set off the length of the hair, and they approved. Then I had to talk to the engineers, because apart from marketing and aesthetics, every Barbie doll was also a technical feat. Our chem lab had just gotten a call from Japan that the factory who could make the special permanently-crimped hair feature was involved in a tragedy with a helicopter crash on Mount Fuji, so we had to find a back-up company and found one in Georgia. At the board meeting, one of our directors suggested the doll came with real ‘Dep’ hair gel. She became the best-selling Barbie of all time.

Introduced in 1959, Barbie, the ‘teenage fashion model,’ was supposed to crystallise the quintessential Californian look and lifestyle. Mattel, headquartered in Los Angeles, conquered not only the American but the global market (and households) with the doll with signature pink clothing and blond hair. But what exactly would one understand as the ‘California’’ style?

CS: When I arrived in LA in 1963, the ‘California look’ was very trendy. I was from Minnesota, so for me it was very clearly different: it had to do with the temperate climate, the laidback coastal ‘surf’ lifestyle, and the presence of natural elements. The bright sunlight was mirrored in strong, bold colours and patterns. A few years before, the American pavilion at the Brussels World Fair had been very successful, showing fashions chosen by Vogue, from over sixty manufacturers from all over the USA, and these were linked to the sporty and modern Californian lifestyle in the public’s mind.

Indeed, in 1958 Vogue US April’s issue, dedicated to the Brussels World Fair (‘Fashion: Belgium 1958 — the land, the new world’s fair, and us — an on-the-spot report’), the fashions presented feature clean, modern lines, some jeans and bathing suits, as well as bohemian blanket-like dresses with capes, and summery polka dots, stripes and floral patterns make up the rows of miniature silhouette images. A plaid cotton bathing suit by Claire McCardell epitomises the ingenuous American mid-century modern style. Occasions for donning the looks are described as distinctly American: sports car meets, poolside parties, city luncheons, tennis games and deep country sweater dressing. The designer list ranges from Cole of California to Philip Hulitar, Mollie Parnis, Jane Derby, Ben Banack, Lilly Daché, Adele Simpson, and more illustrious names such as Arnold Scaasi, James Galanos, Bonnie Cashin, Tina Leser, Claire McCardell and the Brooks Brothers. The patriotic captions read as thus:

‘Most American look on two legs: jeans. Here, at home with a Western shirt.’ Levis

‘Chemise bathing suit and a cut you’d know automatically — American as they come.’ Claire McCardell

‘A tennis dress in white piqué, American classic for American figures.’ Cabana

‘Most American dress in the world: the shirtwaist. This is orange chiffon; afternoons, evenings.’ Talmack

‘Red, white, and still champion: ‘T-shirt’ knit. (50,000,000 dresses can’t be wrong)’ David Crystal.

‘American by choice — the people’s choice: Cardigan-suit idea. This, red and navy-blue Tweed.’ Davidow

‘At-home, slim silk pull-over and sharkskin pants, a touch of Americanitis in the pink.’ B.H. Wragge

*

Having trained and worked at different American fashion brands before, Carol now worked for Mattel in Los Angeles, making mood boards and mock-ups, prototypes and samples for Barbie, just like a normal fashion designer for adults would. I’m curious about what her fashion references were, and whether she visited trade or fashion shows like any other professional.

CS: The type of research I did, and my day to day workday changed per decade, because technology changed. First, magazines were very important inspiration sources, especially for colour and trend reports, Women’s Wear Daily, California Apparel News. At Barbie we also embraced Mary Quant youth fashions when they came out. Then, everything ‘pop culture’ on TV: the program Style with Elsa Klench on CNN (1980-2001) was very important, and also, Charlie’s Angels in the 1970s-80s, Dynasty in the 1980s and Baywatch in the 1990s. All these programs influenced Barbie’s style. For the Malibu Barbie set, I would literally go sit on the Malibu shore and think of Malibu Barbie, Ken, Christie and Skipper, and ride horses with friends along the bluff. I rewatched Gidget with Sandra Dee. Apart from these Californian inspirations, I also travelled widely to Europe in the 1970s, in order to watch people in the streets, and go to some fashion shows.

But was Barbie meant to be a trendsetter or a trend follower?

CS: We had to take into account a fashion that was understandable for a child, and remember that a doll came out one year and a half after designing her and a year after presenting her at the toy fair in Nurnberg. The outfit had to be at a certain point on the ‘fashion curve,’ right after the peak, when it came out. This meant that the market was well saturated with this type of look and the child would recognise the fashion. The play pattern was important, it had to appeal to a mainstream children’s audience. If Barbie was too fashionable or ahead in style, she would lose her appeal.

*

Mattel had started, like so many Californian corporate wonders, as a start-up with its founders Elliot and Ruth Handler selling picture frames from a garage. In the early years, the goal was to make the rigid plastic doll more life-like, such as through the introduction of bendable legs. Engineers from aerospace and ex-military technicians which had lingered in LA after the war, flocked to Mattel, each with their own special skill. Charlotte Johnson was Barbie’s first fashion designer, she taught art history during the day, and designed for Barbie as an evening job. For Carol, too, it was hard to be taken seriously when she had to introduce herself to people as Barbie’s designer, which was not considered a serious profession. ‘It was just laughable,’ she told me. Carol was part of a four-people design team, which grew over the years into a thirty-people team. The group of four designers were always competing with each other to get their designs approved, and communicated with rapid mockups with engineers, for special features like the fabrics that changed colours underwater, and hair colours which changed with water application, already introduced in the 1970s. For the clothes, the designers had free creative reign, and had to make a pattern to be tried out with sample makers, and then adjust and finalise for production. The sewing of the miniature garments, made from fabrics sourced in Asia, was tested in different factories, and were eventually sent off to Japan, where dexterous teams sewing tiny clothes by hand obtained the best results. Each designer cut six sets of patterns for a design review meeting, and then the design would move through different meetings with marketing, children and parent feedback tests and more. All in all the process took up one year.

The in-house motto with regards to the social and physical evolution of the dolls, was ‘Barbie changes as we change.’ Usually, market research had to prove that there was a market for a new idea, and then that change would be approved. The first black doll ‘Christie’ came quite early, in 1968; she was a talking doll (‘You’ll never know what I’ll say next’) and introduced as a friend of Barbie’s. It took until 1980 for a black Barbie doll to be called ‘Barbie’ herself. Carol Spencer had to prove to Mattel it was time to add more dolls with different skin tones to the market: the Magic Curl Barbie Doll of 1981 was the first series of dolls which had a Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic type. Later in the 1980s, a Japanese Barbie doll was made by Mattel’s licensee Takara. This Caucasian doll was different from Barbie to better appeal to the Japanese customer: she had a closed mouth, was shorter in height and had large manga-style rounded eyes. ‘It was a very popular and cute doll but the license was broken and the doll was pulled, since the Japanese managers were somewhat old-fashioned: they did not like this westernized doll with Japanese look and wanted to uphold the ideal beauty of the Edo period.’

Even though Barbies were tested in various settings before being released, Carol learned a lot about desirability, societal norms and expectations from the feedback she got at live events: ‘At a convention in the 1990s, a grandmother once came up to me and asked, where are Barbie’s underpants?, which I thought was a good point, so I designed white lace briefs for My First Ballerina Barbie, together with molded-on ballet slippers and painted white tights, for convenient dressing. The most important thing was always that it had to be easy for a child to dress. Later, Barbie would get flesh coloured undies and permanently fixed underpants.’

Another change which came in the 1990s, was the addition of Chelsea (Kelly), a baby sister doll for Barbie. Barbie could not have a child out of wedlock with Ken, and had to remain eternally unmarried/single or it would stop the play pattern of identification for a young girl. Spencer had suggested that children needed more nurturing features, rather than just projection, so they would play longer with Barbie. Child testing had proven that children grew out of playing with Barbie by age 5-6, with kids starting to play with her as early as age 2.

In her private life, Carol Spencer had to navigate multiple roadblocks to do the type of creative professional work she wanted to pursue, rather than the five predetermined professions for most American women of her generation (teacher, nurse, secretary, shopgirl and seamstress). Spencer convinced the marketing team that Barbie could thus also be more than a nurse or teacher, and already in 1973, she created outfits for new professions: a flight attendant costume and an MD costume with an on-call pager phone. Later, she created Barbie’s astronaut suit, with aviation shoulder pads. As she told me,‘The play value of these professional costumes was high, it was not so much about the fashion. A child could relate to these professions, and that’s what was most important to me. Everything was child tested, and the problem was that children were fearful of space.’ So Carol’s racer suit and even pajamas for Barbie to wear in space were not commercially successful – instead, Barbie turned back to fantasy, in the form of 1980s glamour. The 1981 wedding of Princess Diana, the dramatic costumes of Dynasty, and the fashions of Claude Montana and Thierry Mugler all gave a new high fashion focus to Barbie’s wardrobe after the more sports-focused 1970s.

Carol, whose name started to appear on the boxes of her Barbie designs (a special honour and name credit not easily won) also started to travel more to adult conventions and Barbie fan meetings in the 1980s to sign her dolls, so she convinced the board to create Barbies especially for this growing adult market, which would spend more money and had different tastes than the children’s market. In the 1990s, Mattel had a line called ‘Great Era Barbies’ with historical and film costumes, for which Carol visited the LACMA museum’s collection to learn about period gowns. She designed a Sissi-gown and a Scarlett O’Hara-gown for Barbie, which became very popular with collectors. Barbie with clothes designed by ‘real’ fashion designers followed. The first fashion designer with his eponymous Barbie was Oscar de la Renta: ‘He could choose to either design the doll himself or approve one of our designs. Oscar approved my design, a high glamour, black with gold extravagant dress. He entered the room, nodded at those designs he liked, and left with no words.’ In 1994, Carol created one of her last collectible dolls, Benefit Ball Barbie, for the 35th anniversary of the doll. It was a golden extravaganza, with Carol’s name stamped not just on the box but on the doll in gold lettering. Her final creation before retirement, Café Society Barbie in 1998, wore an Art Deco inspired sheath dress in gold lurex lace over satin. A career which had started with pragmatic, sun-kissed American sportswear came to an end with couture-like, dramatic silhouettes.

Today, after decades of feminist and pedagogic criticisms of Barbie, one can find Barbie dolls in many different body types (petite, curvy, tall), various skin tones, Barbies with disabilities and Barbies with gender neutral professions (such as truck driver Barbie, game developer Barbie, vaccinologist Barbie, and of course, President Barbie). These have been welcome and necessary changes to the Caucasian blonde archetype with tiny waist and unnaturally long legs, which Barbie has represented to so many children and parents over the decades. According to Carol though, the elongated body was not just due to an impossible beauty ideal, but a pragmatic solution to technical and commercial issues: ‘You have to realise that with more diversity in body types, not all the clothes will fit the same Barbie anymore, so you will have to buy different sets. The design for Barbie always had to do with the right scale and the right fabrics, with clean seams and seam allowances, which were very difficult to execute in miniature garments. Often fabrics were too heavy or too thick for a small doll, especially when doubled at the seam. This is also why she has a tiny waist: because the skirt and shirt fabric meet in the middle part, when she lays flat for dressing, there’s often a double piece of fabric there. This is why the waist is smaller than normal, to make it appear normal under several layers of fabric. Then, because children could not fit sleeves on full, upward arms, the arms had to be hollowed out, so there would not be too much fabric at the sleeve inset. And yet another factor is artistic: the proportion of the doll was based on a figure sculpted by an artist, who used the ideal proportion of three heads to the waist, where a normal person is usually 2,5 heads to the waist. The eternal problem was that, even on a tall Barbie, even the smallest buttons were too big.’

*

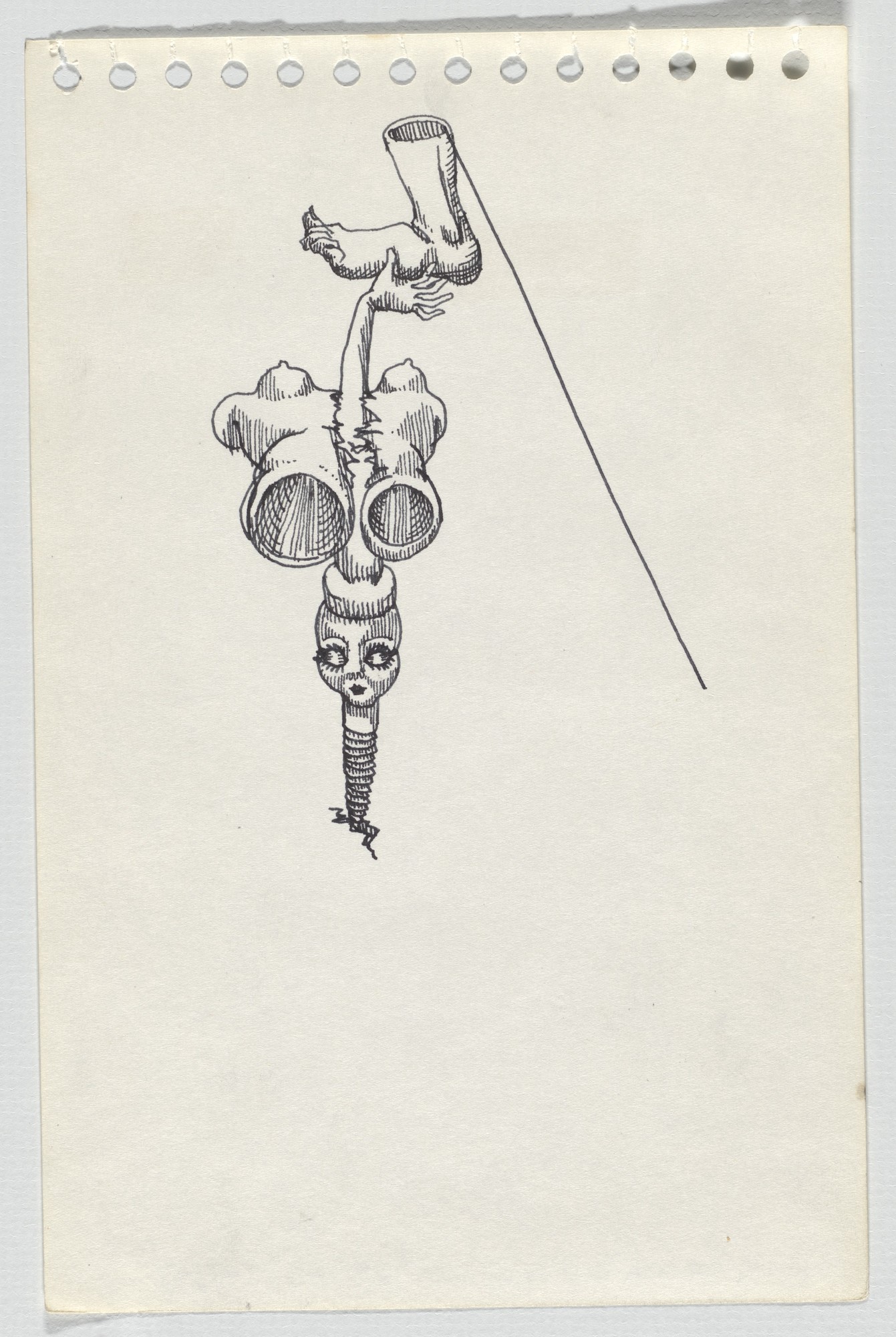

A few years ago, I attended a seminar on fashion and disobedience in Santiago de Chile. One of the workshops was given by Maria Galindo, a Bolivian anarcho-feminist from the collective ‘Mujeres Creando.’ She made head dresses with the participants which deconstructed Latin stereotypes of femininity through tropes such as Carmen Miranda, exotic fruits and Barbie dolls. The result of the workshop were joyous, colourful head dresses full of long-legged Barbie dolls, sticking out like totems of feminist salvation. Nothing more defiant than a carnavalesque headdress full of perky Barbie dolls. I looked through the various dolls on display and found, both to my adult relief and childish disappointment, no sign of Totally Hair Barbie amongst them.

Karen Van Godtsenhoven is a freelance curator and fashion researcher at Ghent University. She greatly enjoyed reading Carol Spencer’s book ‘Dressing Barbie.’